|

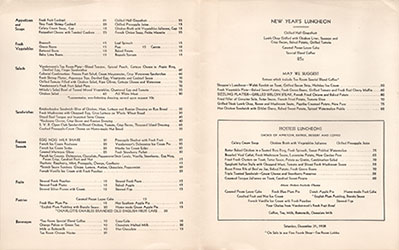

Tea Rooms The first tea room in America opened at Marshall Field's in Chicago in 1890, although Wannamaker's in Philadelphia insists its Crystal Tea Room was first. In the 19th century, ladies shopping downtown returned home for lunch; having lunch at a downtown restaurant unescorted by a gentleman was not considered ladylike. But after a Marshall Field's clerk shared her lunch (a chicken pot pie) with a tired shopper, Field's hit on the idea of opening a department store tea room so that women shoppers wouldn't feel the need to make two trips to complete their shopping. In the first half of the twentieth century, department store restaurants were some of the best places in town to eat. They often did their own baking and made desserts from scratch. They whipped up mayonnaise and produced their own potato chips. Dishes popular through the decades included chicken pot pies, tomatoes stuffed with chicken salad, club sandwiches and frozen fruit salads. Most tea rooms had children's menus; department store restaurants were pioneers in catering to children. And it was as children, accompanied by their mothers, that most St. Louis baby boomers first visited the tea rooms at Famous-Barr, Stix Baer & Fuller and Scruggs Vandervoort Barney. Scruggs Vandervoort Barney Scruggs Vandervoort Barney started out as a dry goods store in 1850. Founders Matthew McClelland and Richard Scruggs opened the original store on North Fourth Street. In 1860, W. C. Vandervoort joined the company. When McClelland retired in 1870, Charles Barney replaced him. In 1907, the owners moved their store into the Syndicate Trust building at Tenth and Olive Streets.

While the new store had floor after floor packed with lingerie, gowns, home furnishings and more, the seventh floor had "no merchandise, nothing displayed and nothing sold, except in the Tea Room, all blue and white and mahogany."

The seventh floor

Tea Room was designed as a place where men and women could "seek the

refreshment that comes from a wholesome, tasty luncheon daintily

served amid quiet and restful surroundings." It was a respite in

between shopping. Telephone service was provided at tables, upon

request. A special area was set aside for smoking to attract men.

In 1920, a new Men's Grill opened on the seventh floor with "the same good service, the same excellent cuisine, as found in the Tea Room." By 1927, Vandervoort's also fed shoppers refreshments and light lunches at a soda fountain on the first floor and a soda fountain and cafeteria in the basement. More meals were served each day at Vandervoort's than at any other place in St. Louis, even though no breakfast or dinner was prepared. By

1933, Vandervoort's had introduced weekly fashion shows

in their Tea Room on Wednesdays from 12:30 to 1:30. Women

could enjoy lunch while being entertained by attractive models,

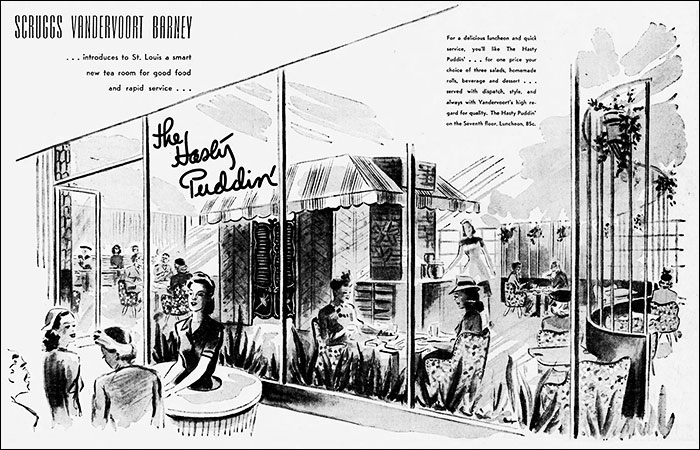

tempting with seasonal clothing. In 1944, Vandervoort’s added to its seventh floor offerings with The Hasty Puddin'.

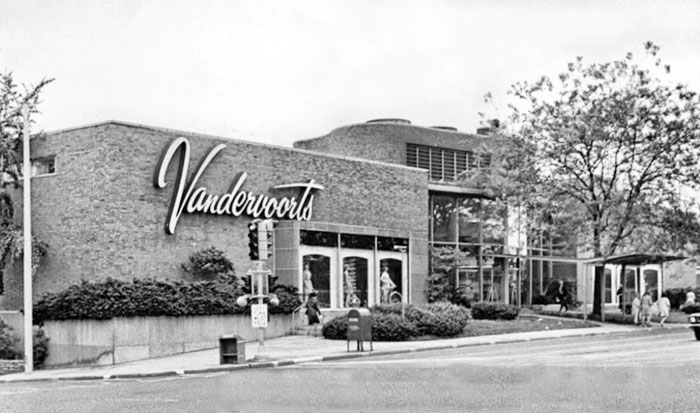

On September 21, 1951, Scruggs Vandervoort

Barney opened its first branch store at the corner of Hanley and

Forsyth, in Clayton.

The entrance to the top floor of the new store

was from Forsyth, while the bottom floor opened on a free parking

area for customers. Each floor was surrounded by a mezzanine, the

upper one housing the store’s restaurant, Forsyth Corner.

Vandervoort's opened its second branch store on August 13, 1958 at the Crestwood Plaza Shopping Center, at Highway 66 and Sappington Road. Its Crestwood Tea Room was located on the upper level.

Stix, Baer & Fuller

Stix, Baer and Fuller,

originally called the Grand-Leader, was a St. Louis institution for

almost a century. Founded in 1892 by Charles Stix, brothers Julius

Baer and Sigmond Baer, and Aaron Fuller, they moved their

Grand-Leader department store to the corner of Broadway and

Washington Avenue in 1897. With the tagline

"The Fastest Growing Store in America" the building did in fact

become too small, housing the department store only until 1906, when

it moved to Sixth and Washington Avenue.

The new Grand-Leader building had eight floors and 60 separate departments. The store was hailed as modern and progressive in its design. Department stores in the 20th century were attempting to establish themselves as civic institutions rather that profit driven businesses. To accomplish this and to lure in their mostly female clientele, the store incorporated free public telephone service, waiting and writing rooms, as well as manicurists, hairdressers, bathrooms on almost every floor and even "hospital rooms" staffed with physicians and nurses. Grand-Leader's "tea room" was on the sixth floor. It occupied the entire front of the building on the Washington avenue side and seated 750 comfortably. It was decorated in gold and blue, with the waitresses dressed to match.

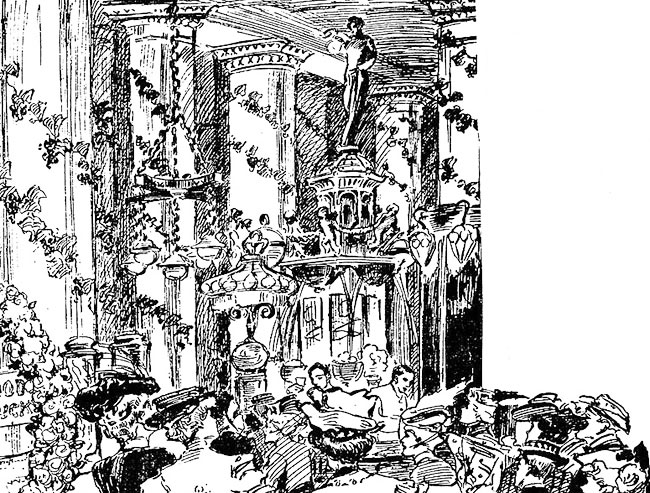

A more spectacular eating venue, located

centrally on the main floor, was a gorgeous octagonal-shaped soda

fountain. It seated 100 customers around a 21-foot-tall mirrored

column topped with a bronze statue of the goddess Plenty. At her

feet was a circle of dancing cupids surrounded by a circle of

dolphins with water spouting from their mouths into tiny glass

bells. This proved to be a focal point for women to meet and

socialize in the store.

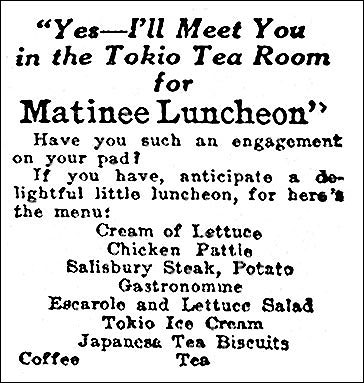

In 1911, Grand-Leader remodeled their sixth floor dining space and reopened it as the Tokio Tea Room.

In 1929, Grand-Leader – now known as Stix, Baer & Fuller – revamped its sixth floor tea room, converting it into two spaces. The Moderne Room was a new modernistic tea room "in delicate shades of green and orchid with striking mural decorations – for chic feminine tastes." The English Grill was more masculine in decor, with colorful hunting pictures, massive oak tables, and chairs upholstered in deep red leather.

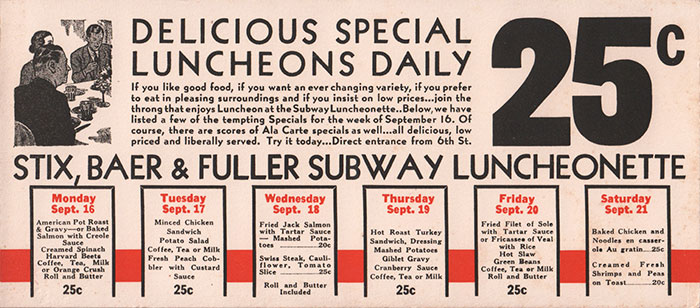

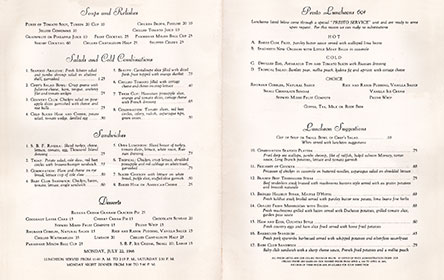

By the mid

1930s, Stix offered 25¢ lunches in its basement Subway

Luncheonette, in addition to its main floor Fountain and its two

sixth floor venues.

By the late 1940s, Stix, Baer & Fuller's sixth floor

dining space was home to the highly regarded Missouri Room. The more

casual SBF Fountain, which featured soups, salads and sandwiches,

resided on the first floor.

In 1955, Stix, Baer & Fuller expanded into the suburbs with a four-story building in the new Westroads Shopping Center at Clayton Road and Brentwood Boulevard in Richmond Heights.

The Stix Westroads tea room was the Garden

Room, located on the second floor, overlooking Clayton Road. It was

known for its Encore Salad — iceberg lettuce, Swiss cheese, turkey,

bacon and a honey mustard dressing. On the side was an alligator roll

— a roll with a crackled top crust, resembling alligator skin. Other

favorites were the

frozen fruit salad, served with chicken salad sandwich wedges,

and

chiffon Jell-O, served as a side dish with a cold sandwich or as

a dessert.

Additional branch stores followed — River Roads (1961), Crestwood Plaza (1967), Jamestown Mall (1973), Chesterfield Mall (1976), Northwest Plaza (1978) and St. Clair Square (1979). All had the same Garden Room restaurant — except for River Roads.

Stix, Baer & Fuller's River Roads store opened

in the summer of 1961 at Halls Ferry and Jennings Station roads in

the River Roads Mall. A separate building, overlooking a sunken

garden, housed the Pavilion Restaurant.

The Pavilion Restaurant was open seven days a week for lunch and dinner. Two live trees, eight feet and twelve feet tall, were featured in the glass-walled center section. A pool, with a sculptured marble fountain, added to the garden atmosphere. The main dining room was French Provincial in feeling, with antiqued walnut chairs and star-flecked, deep blue carpeting. An informal patio area had a flagstone floor and wrought iron furniture in pale blue. Lighting was rheostat controlled and could be focused on models when a fashion show was in progress.

Famous-Barr In January of 1912, the Famous Clothing Company and the William Barr Dry Goods Company merged to form the Famous & Barr Company, at Washington Avenue and Sixth Street. In conjunction with the merger, they announced the erection of

In September of 1913, the Famous & Barr Company

formally opened its new store in the first eight floors of the

massive Railway Exchange Building at 611 Olive Street.

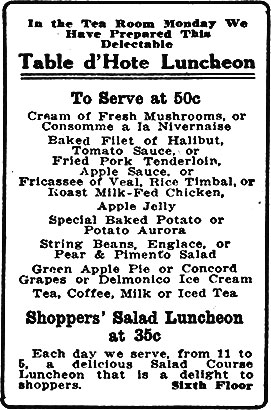

Famous & Barr had a tea room as early as 1913, first in their store at Washington and Sixth Street, and then on the sixth floor of their new store in the Railway Exchange Building.

The sixth floor Tea Room featured live music.

Both table d'hote and ala carte menus were available. Starting in

1915, women customers were entertained during lunch by a Fashion

Revue.

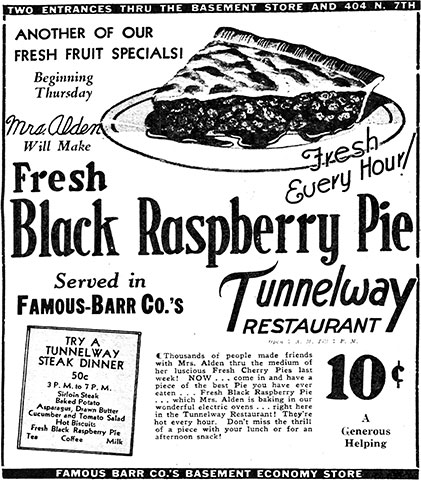

In 1929, Famous-Barr opened its Tunnelway Restaurant, billed as "that different eating place under Locust Street." There were two entrances, one though the Basement Store and one at 404 North Seventh Street. The Tunnelway, open daily from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. for breakfast, lunch and dinner, featured "Mrs. Alden" and her pies.

The Tunnelway

Restaurant was a staple for Downtown St. Louis shoppers and

non-shoppers through at least 1977.

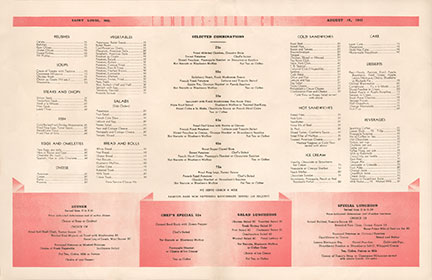

The sixth floor Tea Room

continued on as Famous-Barr's main dining room, offering a large

array of luncheon options. A 1942 menu featured "Onion au Gratin"

soup for 25¢ — the forerunner of a Famous-Barr classic. In late 1953, the sixth floor Tea Room was redesigned and converted into two distinct venues. The more casual Rose Room was "designed for people short on time" and served complete luncheons for 95¢.

The more formal of the two venues was the St. Louis Room, its curving colonnaded walls adorned with murals spanning a century of St. Louis growth from river town to modern metropolis.

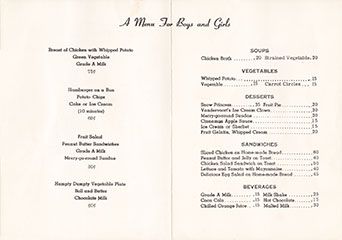

While the St. Louis Room was cloaked in formality, it still catered to children, or more politely, juniors. Department store tea rooms, where the principal patrons were women, were the first to focus on children as guests. Printed children’s menus, based on the idea that children liked to choose their own meal, arrived in the 1920s. Vegetable plates were common from the 1920s through the 1940s. Creamed chicken was typical on children’s menus before the 1950s. Hamburgers weren’t found very often until after World War II. In 1977, Famous-Barr opened Papa FaBarre's in its downtown store. Located off the second-floor men's department, it was a place for husbands to have a beer while their wives shopped on other floors for nylons, bras and other unmentionables. The ornate mahogany bar was from an old Gaslight Square saloon. Other decorations, including the belt-driven ceiling fans, brass cash register and stained glass, were all antiques.

The restaurant was named after an entirely fictitious turn-of-the-century gourmand, Giuseppe FaBarre. Photographs decorating the bar told his story — from his wild days at Cornell to his crowning achievement as grand marshal of "the Parade of Restaurants" at the 1904 World’s Fair. The space had previously

been the department store’s barbershop and "FB" was etched in

the windows. The restaurant's designers wanted to keep the old

windows, so they made up the name FaBarre. But Johannes

Verdonkschot, Famous-Barr's food service director for 15 years,

was responsible for the fictitious biography. Papa FaBarre's menu included sandwiches and salads, plus a choice of turtle, lentil or oxtail soup. Bar offerings included Papa's Bird Bath martini. In 1944, Famous-Barr announced plans to expand into the suburbs.

In 1948, Famous-Barr opened its first branch store at Forsyth and Jackson, in Clayton. The three-story modernistic structure featured an elaborate tea room on its third floor, known as the Wedgewood Room.

Famous-Barr's imposing three-story Southtown store opened at Kingshighway and Chippewa in 1951. It featured the Mississippi Room for dining on the mezzanine below its main floor.

Famous-Barr's Northland store opened at West Florissant and Lucas-Hunt Road in 1955, completing the final phase of the company's proposed postwar expansion. Its Jade Room, designed for leisurely luncheons, was located on the mezzanine between its main floor and basement. But there were more branch stores and tea rooms to come. In 1963, Famous-Barr's South County store opened at Lindbergh and Lemay Ferry Road. It featured three eateries — the buffet-style Carousel Room and the Marionette Room on the mall level, and the Snack Bar on the lower level. In 1966, Famous-Barr opened its Northwest Plaza store at Lindbergh and St. Charles Rock Road, with the Golden Eagle restaurant and adjoining Pilot House coffee shop on the mall level. When Famous-Barr opened its store in the West County Shopping Center at the intersection of Manchester and Interstate Highway 244 in 1969, it featured the upscale Mauretania Room. The 120-seat restaurant was elegantly furnished and decorated with hand carved walnut paneling, moldings and cornices from the Cunard Line's R.M.S. Mauretania.

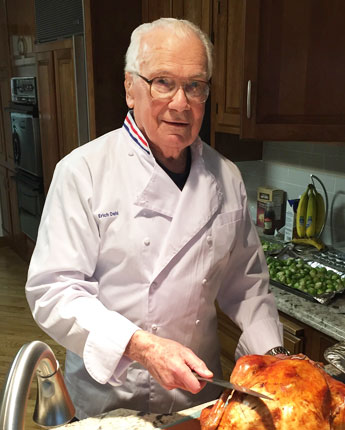

Perhaps more distinctive than Famous-Barr's tea rooms themselves were two items on their menus — the French onion soup and John White burger. There's ongoing debate as to who gets credit for Famous-Barr's iconic French onion soup. Chef Manfred Zettl often gets the nod, but he became Famous-Barr's Executive Chef in 1963, while "Onion au Gratin" soup was on tea room menus as early as 1942. Thomas Ferrario was Executive Chef throughout the 1950s and Erich Dahl was Director of Food and Beverage. Both had a hand in creating the soup which Manfred Zettl perfected. The soup was thick and rich, and came from the kitchen in a McCoy pottery brown drip soup bowl, bubbling with melted Gruyere cheese atop two slices of French baguette. The cheese was so thick and stringy when spooned, it was a challenge to get it into your mouth.

Chef Erich Dahl created Famous-Barr's John White burger. Dahl tells the story of a cook at the Clayton store named John White. In those days, there were new menus every day, with menu items named for employees. White wanted something named for him too. The result was the John White burger. Eventually, the burger was offered at all Famous-Barr restaurants. It stayed on the menu until White died and his heirs sued over use of his name. The secret to the burger was the onions. According to Dahl, they were sliced thinly, then cooked in ½ inch of hot oil or shortening and removed when they were brown. If they were cooked too long, they became bitter. The burgers were grilled or broiled hamburger patties, made from ground beef that was 85 percent lean. They were assembled on a toasted bun, with the onions and a rarebit sauce thick enough to stay on the burgers. The sauce included American cheese, dry mustard and Worcestershire sauce.

* * * * * Modernity eventually made department store tea rooms obsolete. The times changed and so did the pace of life. Women no longer had time to linger. It was no longer glamorous to park inside a stuffy tearoom next to the lingerie department. Stores closed or revamped their large, elegant tea rooms, switching to speedier bite bars, cafeterias and food courts. People still got hungry when they shopped, but now they had other options. An era had ended.

Copyright © 2023 LostTables.com |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||