|

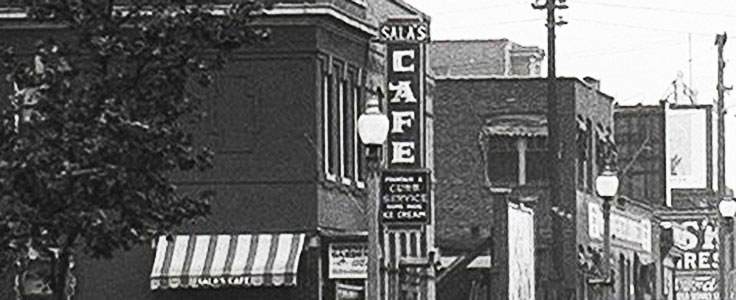

Sala's Angelo Sala was born on July 8, 1887 in the small Italian village of Castelletto, approximately 25 miles west of Milan. He emigrated to the United States in September of 1904 and, before year's end, set out by train for Minnesota. When his train was forced to stall in St. Louis by a snowstorm, the 17-year-old Sala, who spoke no English, disembarked at Union Station with immigrant tags around his neck, trying to figure out what to do next. Sala met a man named Charles Galli at the train station. Galli was a saloon keeper who, by 1907, was living above his saloon at 5100 Daggett. Galli convinced Sala to come to his home on the Hill. Angelo Sala would live on the Hill for the rest of his life. The 1908 St. Louis City Directory listed Sala's occupation as a laborer. The 1910 census stated he was a saloon keeper, perhaps with a saloon on the St. Louis levee. In 1911, Angelo Sala opened a saloon at 1933 South Kingshighway, less than a half mile east of Charles Galli's. Sala lived above his saloon, first alone and then with Galli's daughter Emma, who he married in 1912.

In time, Angelo Sala's

saloon morphed into a restaurant known as Sala's Cafe. It was

located on the northwest corner of Kingshighway and Daggett, just

north of the Missouri Pacific railroad tracks and crossing

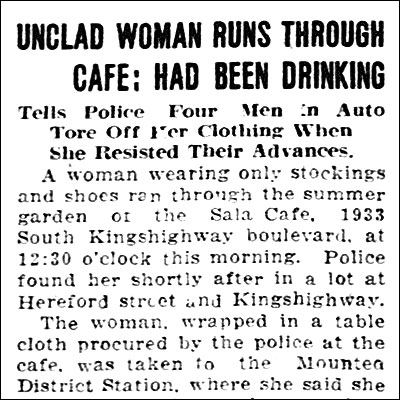

gates. As was the practice by many restaurants in the days before air conditioning, Sala's Cafe had a summer garden where customers could eat and drink outdoors. There was often entertainment, some of it unplanned, as reported in the July 2, 1927 St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Angelo and Emma Sala had seven children; Theresa was born in 1913, Angelo Jr. in 1917, Mary in 1918, Charles in 1919, Louis in 1921, Fermo in 1923 and Josephine in 1926. They all lived above the restaurant and helped out downstairs when they were old enough. The restaurant had two large rooms, one of them used for private events and parties. Angelo Sala claimed he started curb service in St. Louis. He would take food and drink to women, who were barred from the saloon, as they waited outside in their horse-drawn buggies. It became a regular feature for a time.

On July 26, 1936, the following notice appeared in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

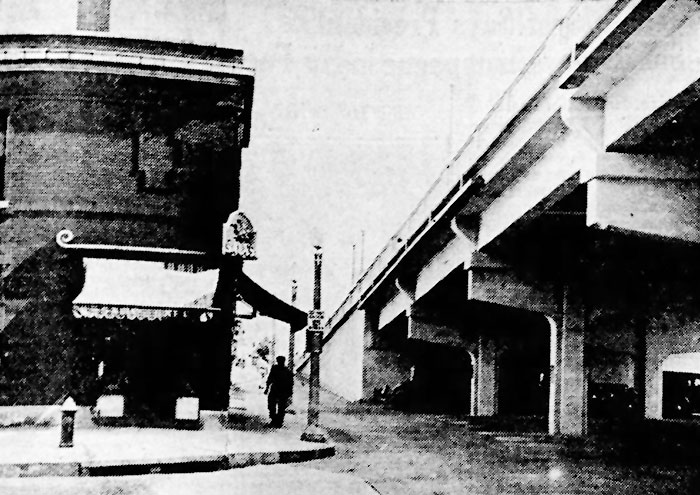

The railroad

crossing, just south of Sala's Cafe, was known as one of the

most dangerous in the city. Its elimination was part of the city's

safety campaign to remove all grade crossings. The viaduct, which ran between Southwest and Shaw, was completed in August of 1937. It was formally opened to traffic on the afternoon of August 14 in ceremonies led by Mayor Bernard Dickmann.

About 1000 persons gathered at the south end of

the viaduct and cheered as Dickmann cut a white ribbon to signify

the official opening of the concrete bridge. An automobile parade

moved slowly up the incline, and the spectators walked up along the

side of the six-lane roadway. When the procession had passed, the

street, blocked for a year during construction of the viaduct, was

opened to traffic.

Days after the new viaduct had opened, Angelo Sala filed suit against the City of St. Louis for $90,000, charging the new Kingshighway bridge had ruined his business. He claimed that the new viaduct had cut off normal access to his cafe. The grade of Kingshighway was now 25 feet higher than it formerly was, forcing customers to use a narrow, one-way lane on the side of the new structure. Northbound traffic on Kingshighway now had to pass right by the cafe, above its front door. To get to the restaurant, it was necessary to make a left turn into the narrow side lane. Sala also pointed out that before construction of the viaduct, the cafe had a big parking space on Kingshighway for the convenience of his customers. Now there was no room for parking.

On December 15, 1938, a verdict for $45,000

damages was returned by a jury in favor of Angelo Sala. All the

publicity actually helped business, as customers had no problem

finding the restaurant or parking. Sala rebranded his restaurant: Sala's / Under the Viaduct.

Sala's survived the Depression, Prohibition and the war years. The restaurant was busy during World War II, when at times it operated 23 hours a day, serving round-the-clock shifts of workers at nearby businesses converted to war plants. All seven Sala children worked at the restaurant. Mary and Charlie lived with their spouses; the other five never married and continued to live upstairs with their parents. Downstairs was the clatter of heavy plates and the crashing of dumped silverware. A small American flag fluttered in the artificial breeze of an air duct above the bar. A small sign sat atop a pay telephone: "Piano rolls can be played after 7:30 p.m. Hand playing anytime." Sala's was know for its sandwiches, steaks and pastas. Its menu included Mongol soup, a blend of bean and split pea, homemade ravioli and ice cream, and 16-ounce mugs of beer. It also offered one of the best St. Louis sandwiches ever – the Sala Special.

In the October 27, 1976 St. Louis Post-Dispatch it was announced that Sala's would be closing on October 29. There were multiple reasons for the closure. Theresa Sala, the oldest of the seven Sala children, said, "Just say economics." Angelo Sala Jr. said it was the loss of nearby industries. Louis Sala said it was the westward move to the county. Eighty-nine year old Angelo Sala Sr. had his own thoughts.

Louis Sala added, "It's the night business,

it's gone, gone out west. And anybody can cook a steak; it doesn't

take brains to cook a steak."

Angelo Sala, Sr. died on November 30, 1977 at the age of 90. Emma Sala died on Septmeber 13, 1986.

The Sala estate sold the building at 1933 South

Kingshigway in 2000. In 2001, it became Space, a restaurant owned by

Lee Redel and John Rice, and it's currently occupied by Oliva, a

cafe and event venue – doing business under the viaduct.

Copyright © 2021 LostTables.com |