|

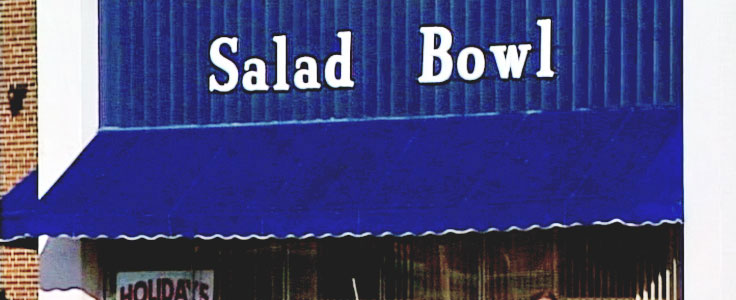

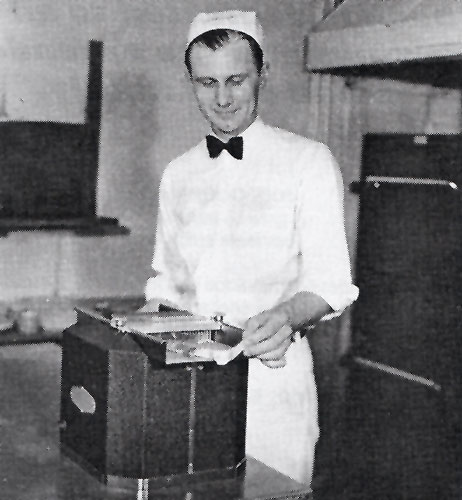

Salad Bowl Elmer Roy Sewing was born on September 5, 1908 in Friedheim, Missouri, about 30 miles northwest of Cape Girardeau. He lived with his family on his father's farm until just prior to his twenty-first birthday, when the August 1, 1929 Perry County Republican reported that, "Elmer Sewing went to St. Louis to look for a job."

By April of 1930, Sewing was living as a roomer

at 1546 Mississippi Avenue in St. Louis and working as a hotel

elevator operator. Not long thereafter, he moved on from elevator

operator to dishwasher at the Miss Hulling's cafeteria at Eleventh

and Locust.

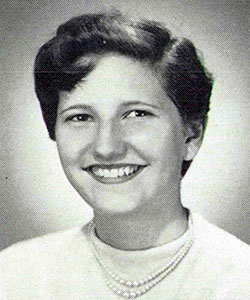

Anna Lillian Poluski was born on April 3, 1910 in Livingston, Illinois. By April of 1930, she was living in St. Louis and working as a counter girl at the Miss Hulling's cafeteria at Eleventh and Locust ― where she met and fell in love with Elmer Sewing.

Miss Hulling's had a company policy against coworkers marrying. So in 1934, Elmer Sewing and

Anna Poluski eloped. They would go on to have four children ― Donna

was born in 1937, the twins, Norman and Norbert, in 1940, and David

in 1945.

While working at Miss Hulling's, Elmer Sewing learned the restaurant business from the bottom up. Norbert Sewing chronicled his father's rise in the Hulling organization.

In early 1948, Sewing enlisted Agnes Lemanski, a frequent customer at Miss Hulling's, to back him in opening a small restaurant at 4203 Lindell, at the corner of Whittier. He called his restaurant the Salad Bowl. The 1,400 square foot establishment seated a maximum of 30 patrons at 4 tables and 10 counter stools. It was so small, when the pantry door opened, it hit the dishwasher. The Salad Bowl was open Monday through Saturday, from 6 a.m. to 5 p.m. Anna Sewing's brother, John Poluski, was the first chef. Fondly referred to as Uncle Johnny, he had also worked at Miss Hulling's. His home-style cooking served as the basis for the Salad Bowl's recipes until the day it closed. The Salad Bowl's baked goods were prepared by "Grandma Pauline," another former Miss Hulling's employee. She baked square cakes and pies in her home. As the Sewing boys grew older, it became their job to pick up the fresh baked goods and deliver them to their father's restaurant.

As the business flourished, it became evident

the restaurant needed to expand. The April 1, 1951 St. Louis

Post-Dispatch reported that Elmer Sewing and Agnes Lemanski had

leased a one-story brick building at 4057 Lindell, just east of

Sarah. By 1952, Sewing had opened the Salad Bowl Cafeteria in the

space.

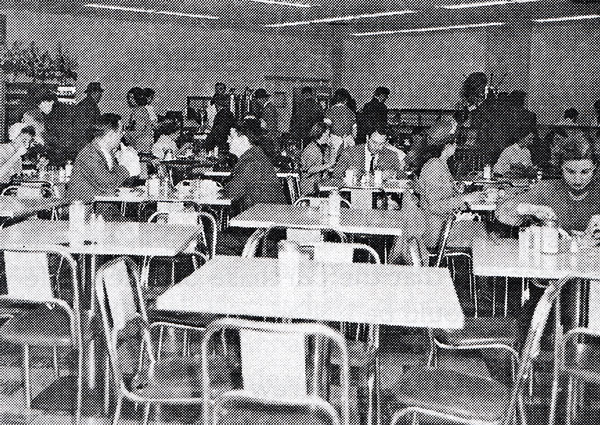

The new location encompassed 13,000 square feet, with seating for 176 diners. Evening hours were extended until 7:30 p.m. On Sundays, the Sewing boys ― first Norman and Norbert, and later David ― would help their father at the restaurant with whatever was needed. They would sweep and mop the floor, wash dishes left over from the day before, wipe down counter tops, peel potatoes or whatever else their dad asked them to do.

The Salad Bowl developed a reputation for

consistently good, home-cooked meals, served in a friendly, family

oriented environment. However, the restaurant was at a disadvantage

as there were only five parking spots. The Sewings needed a new

location with more parking spaces for their customers.

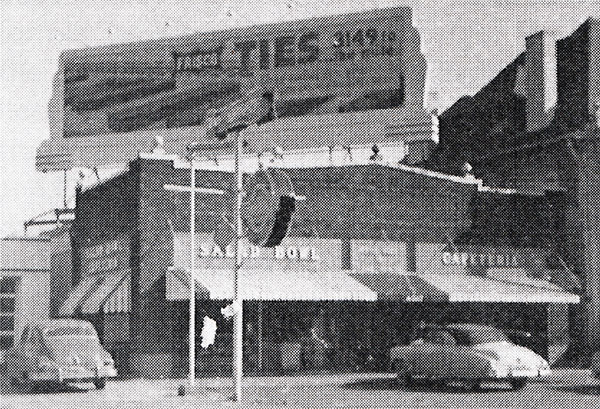

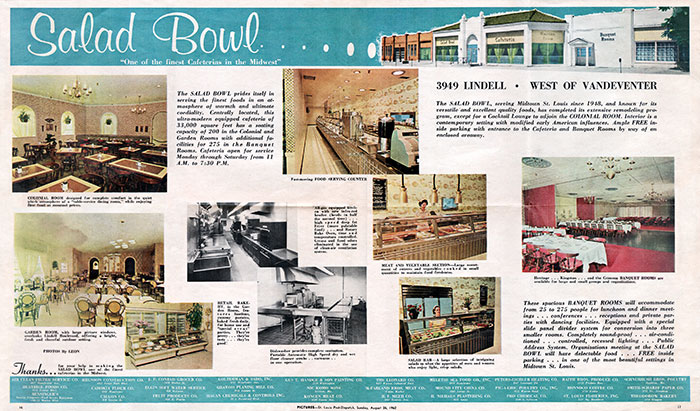

What better place to find parking spots than an automobile dealership. In 1962, Elmer Sewing leased the vacant Lindell Motor Company, a DeSoto-Plymouth dealership at 3949 Lindell, and renovated it for his third restaurant. The new Salad Bowl Cafeteria had 33,000 square feet of floor space. A garage at the west side of the building provided 16,000 square feet of covered parking. Inside, the walls had been refinished with a vinyl simulating the beige and white of old brick. Arches at intervals were decorated with hanging baskets of ferns. A vinyl mural presented an array of fruits and vegetables. One dining room was called the Colonial. Adjoining the Colonial Room was a cocktail lounge. Another dining room, in yellow, was called the Garden Room, equipped with garden-style furniture. A retail bakery in the Garden Room featured pastries baked fresh daily for home use. The two dining rooms provided seating for 200 customers.

Banquet rooms were

more formal. The main one could be divided into three when required by

folding red doors. Red carpeting, antique brass chandeliers and

furnishings created a festive atmosphere. The room was

soundproofed so public address systems could be used. It accommodated from 25 to 275 people for luncheon and dinner

meetings, conferences, receptions and private parties.

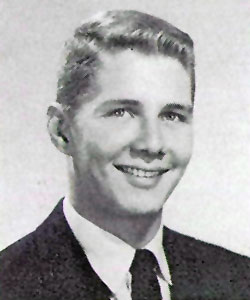

When the Salad Bowl moved to its new location,

the Sewing twins were just finishing college. Norman had plans to be

a dentist and Norbert was planning a career in the Army. But their

father convinced them his expanded restaurant could not succeed

without their help. So after a stint in the military, the twins

joined their father in running the business, as did David after he

graduated college.

The Salad Bowl's cafeteria line was a long one, but it was heavily staffed and moved quickly. The menu focused on standard cafeteria comfort food. There were a dozen or more entrees to choose from, plus a dozen vegetables, two dozen desserts and all sorts of salads. On a typical day, entrees included liver and onions, prime rib, cube steak, top round of beef, chicken chop suey, sauerbraten, chopped beef steak with mushroom gravy, barbecued pork steaks with Elmer's barbecue sauce, salmon patties, stuffed whitefish, scallops, fried catfish, sole and shrimp. Two soups were available each day. Vegetables and sides included baked beans, macaroni and cheese, kidney bean salad, German potato salad, fried eggplant, candied sweet potatoes and potato pancakes. Initially, none of the Salad Bowl's recipes were written down; they were all in Uncle Johnny's head. When David Sewing began working at the cafeteria, he decided to document the recipes.

Over five years, David arrived at the Salad

Bowl each morning at 4:30 to shadow Uncle Johnny. Each "pinch" or

"handful" of an ingredient was put in a bowl and measured before

Johnny was allowed to throw it into the cooking pot. Eventually,

each recipe was dutifully recorded.

In 1968, the Sewings opened a lounge in a

converted store room off the parking garage. They called it "Bits 'n

Saddles." It was decorated as a comfortable living room, with

leather couches, wingback chairs and a crackling fireplace. Liquor

was served to lure customers in after work for a "happy hour" or for

dinner. Bits 'n Saddles remained open for 10 years.

Elmer Sewing often said he was opposed to segregation. But early on, like many restaurant owners, he turned black diners away from his cafeteria, fearing that white customers would not accept them. The following appeared on November 12, 1960 in the "Letters from the People" section of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

When the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964 making it illegal to refuse service to patrons based on race, the Salad Bowl was one of the first restaurants in St. Louis to integrate. According to Norman Sewing, this was more in line with his parents' values.

On June 6, 1976, Elmer Sewing died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 67. Elmer Sewing had kept the "inner secrets" of the business to himself. He was the one who had talked to the lawyers and the accountants. Anna and the boys were left to run the Salad Bowl without him. They started by hiring more employees. At one point, a staff of 100 worked at the cafeteria. Over the years, an effort was made to hire employees with hearing impairment and other disabilities. In 1977, the Sewings purchased the building they had been leasing. In 1980, they began buying adjacent property in order to construct a rear parking lot. Knowing they had to expand the business, the Sewing brothers encouraged greater use of their banquet rooms. To draw customers, they made the rooms available for free to various groups if attendees went through the cafeteria line. Churches, businesses and community organizations used the Salad Bowl's banquet rooms. It was a melting pot of all ages, races and religions.

The cafeteria was located halfway between St.

Louis University and Washington University, and their associated

hospitals. The banquet rooms became popular sites for talks and

lecture series.

If a politician wanted to reach a grassroots

audience in St. Louis, the Salad Bowl was on the short list of

venues. Both Kit Bond Republicans and Thomas Eagleton Democrats

spoke to constituents at the restaurant. Jesse Jackson addressed a

group in 1991 and made a lasting impression on the Salad Bowl staff.

Anna Sewing worked with her sons at the Salad Bowl until she retired in 1992. She died on October 8, 1996 at the age of 86. The Salad Bowl was an integral part of the extended Sewing family's life. Norman's wife Susan, Norbert's wife Doris, and David's wife Julie all had vivid memories of raising their families with the cafeteria as a backdrop. Norman Sewing's son Stephen captured these memories in his book, Recipes of Life: Stories from the Salad Bowl Cafeteria.

In the summer of 2005, the Sewing brothers received an offer from a Dallas developer to buy their building at 3949 Lindell to make way for an apartment building. Norbert Sewing explained why the offer was accepted.

December 23, 2005 was closing day for the Salad Bowl. The Sewing family had been dishing out home-style cafeteria food at three locations on Lindell Boulevard for almost 58 years. According to Norbert Sewing, the Salad Bowl was more than a business.

Copyright © 2023

LostTables.com |