|

River Queen St. Louis began its love affair with riverboats in the early nineteenth century. By the middle of the century, over 2,500 steamboats were arriving at St. Louis wharfs each year. A combination of magnificent floating palaces and plain sturdy packets carried thousands of passengers and millions of tons of cotton, grain, coal and livestock up and down the Mississippi. By the time the twentieth century arrived, the steamboat tide was ebbing rapidly. The railroads had cut deeply into their long-haul business, forcing the steamers to concentrate on short-run service. Finally, the advent of paved highways reduced this endeavor to an unprofitable level, as trucks and busses rolled into the short-haul field. After the turn of the century, the remaining steamboats on the river turned to less utilitarian activities. Some, such as the S.S. Admiral, became excursion boats. And many found their final mooring place as floating bars and restaurants. * * * * * The River Queen was built in 1923 by Howard Shipyards in Jeffersonville, Indiana for the Eagle Packet Company of St. Louis. Originally christened the Cape Girardeau, the steamer carried passengers and freight between St. Louis and Louisville.

In 1935, the Cape Girardeau was sold to the

Greene Line for $50,000. Renamed the Gordon C. Greene, it operated

as a successful tourist boat on the Ohio River between Cincinnati

and New Orleans. The Greene was also a movie star. The riverboat

appeared in Steamboat Round the Bend, with Will Rogers, and

Gone with the Wind, with Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh.

The Greene was sold in 1952 to a group in Portsmouth, Ohio who used the boat as a

floating hotel under the name Sarah Lee.

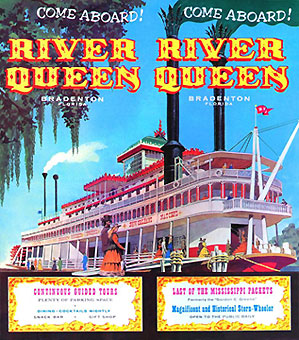

Starting in 1955, the steamer was used as a restaurant and museum by

multiple owners, first as the Sternwheeler at Owensboro,

Kentucky and then at Bradenton, Florida, where it was

rechristened the River Queen.

A bust as a tourist attraction in Bradenton, the sternwheeler was towed to New Orleans in 1960 to become a theater and bar. It didn't fair any better there, and in 1961, the River Queen was put up for auction. * * * * * John Groffel of St. Louis and Arthur Krato of Hannibal were hunting and fishing companions. They also shared a fondness for the Mississippi steamboat era of Mark Twain. When they learned the sternwheeler River Queen was to be auctioned in New Orleans, they decided to buy it. The two would-be rivermen bought the River Queen at auction for $49,100, which they thought a bargain. They felt even better when three days later they were offered $150,000 for the boat. Groffel and Krato chose to dock their steamboat at Hannibal. "I’m told that tourists are the second biggest industry in the state," reasoned Groffel. "We thought about putting the River Queen at St. Louis. Maybe the Arch and the riverfront will draw 3,000,000 people a year. But Hannibal’s the right place for the boat because of the town’s association with Mark Twain. If the 3,000,000 want to see it they have to drive only 90 miles."

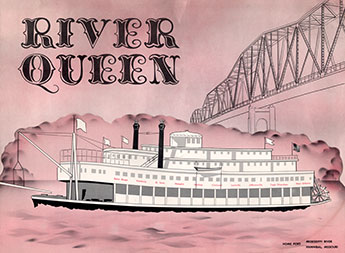

The River Queen arrived in Hannibal in August

of 1961. The 237-foot sternwheeler was moored 200 yards

off US Highway 36 near the Illinois approach to the Hannibal bridge

over the Mississippi. Groffel and Krato were betting a boat that had

failed to show a profit in many other berths could succeed as a

floating restaurant at Hannibal, with a museum and

souvenir shop.

The River Queen opened for business on April 26, 1962.

"We’ve got $157,700 in her so far," said Groffel. He estimated 30,000 people visited the sternwheeler in

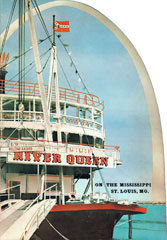

its first three months of operation But two years later, the River Queen was on the move again. In June of 1964, Groffel and Krato had their steamboat towed from Hannibal to St. Louis. They decided to move the 41-year-old craft downstream because of "potential business and interest in river lore in connection with the Gateway Arch and the riverfront square proposed by Walt Disney."

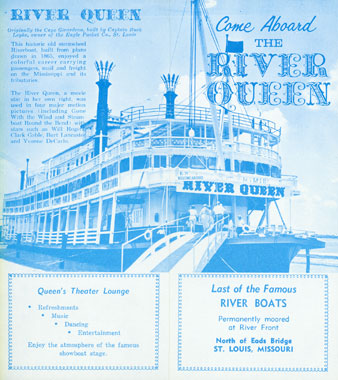

Before opening for business on the St. Louis

riverfront, the River Queen underwent extensive renovation.

The interior was altered to expand its facilities and to comply with

more stringent fire regulations required in St. Louis. A small

theater and lounge were fitted out where the boat's broilers

once stood. Heating and air-conditioning was installed

on the boat to ready it for year-round operation. By December of

1964, the sternwheeler was moored at its final home, just north of

Eads Bridge.

On Friday evening, December 18, 1964, the River

Queen opened to a benefit dinner for the new St. Anthony’s

Hospital. Its main deck restaurant was again ablaze with activity.

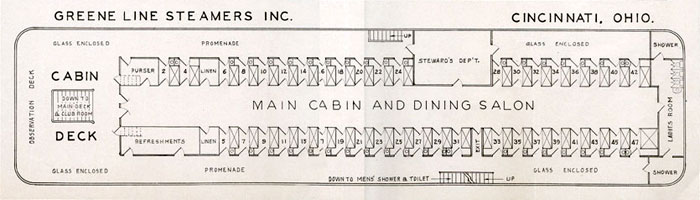

On the Gordon C. Greene, the first-class staterooms

were to port and starboard on the main deck, with the dining salon

occupied the passageway in between, about 30 feet wide.

When the Greene was transformed from a

functioning tourist boat to a floating restaurant, the staterooms

were removed and the dining room commanded

the entire area midship, seating 185 diners.

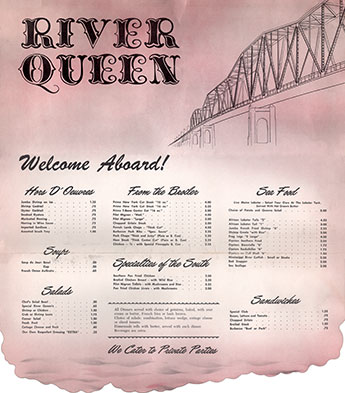

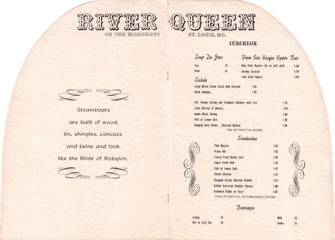

The River Queen had an upscale menu. Live lobster was commonplace. So was catfish; about 700 pounds a week were served. "The fellow we buy the catfish from thinks we’re throwing it overboard," said Groffel, "but you’d be surprised what a national reputation Mississippi River catfish has. Tourists ask for it."

The restaurant was

open for lunch and dinner. Diners were treated to

nineteenth-century-style riverboat splendor.

In addition to its main restaurant, the River

Queen had a cocktail lounge on its upper deck, where lighter

refreshments were served.

The River Queen flourished for three years on the St. Louis riverfront. Then, early on the morning of December 2, 1967, the floating restaurant began sinking. By dawn, its stern appeared to be resting on the sloping river bottom, giving the abandoned craft a sharp list to port.

The restaurant manager told police he first

noticed the boat listing about 3 a.m. when he heard dishes crashing

to the floor. Within three hours, water was at the level of the

second deck ceiling at the stern, inundating part of the second deck

lounge.

Owners Groffel and Krato were called and sat in

an automobile on the waterfront in a steady rain for several hours.

They morosely watched the darkened, fog-shrouded boat settle. They

were unable to explain what had happened. "If it goes," Groffel

said, "I'll turn my back on the river."

Although salvage was attempted, high water and

floating ice made saving the old boat impossible. The contractor

engaged to raise the sternwheeler finally abandoned the project. The

city later brought in a scoop shovel and demolished what remained of

the River Queen, leaving only the steel hull in place.

Copyright © 2022 LostTables.com |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||