|

Pope's Cafeteria Harry Allen Pope was born in Weymouth, Massachusetts on November 17, 1887. His father, Edwin Pope, was a principle in the Pope Rand Company, a shoe manufacturing business in Brockton, Massachusetts. By age 20, Harry Pope had a "traveling position" with his father's company. In April of 1908, those travels found him in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where he was arrested and charged with burglary.

Pope was accused of stealing an assortment of

revolvers and razors, six dozen fountain pens and two dozen

pearl-handed knives. He was connected to burglaries in multiple

cities in multiple states.

After pleading not-guilty, Pope confessed to his crimes. On July 20, 1908, he was sentenced to one year in the Pittsfield house of correction and then three months at Deer Island in Boston. On his release from prison, Harry Pope returned to his hometown of Brockton, working as a foreman in his father's shoe manufacturing factory. On April 23, 2010, he was married in the home of his parents to Luella Wardwell, who was also employed by the Pope Rand Company. On November 24, 1910, their first child, Edwin Kempton Pope, was born. * * * * * In 1911, Harry Pope came to St. Louis to work with the International Shoe Company. He had planned to stay for only a year before returning to Brockton. But during that year he became concerned about the quality of the food available to the workers. He developed a program of pre-ordered hot meals which were first delivered to employees during their lunch hours and, later, served in company dining rooms.

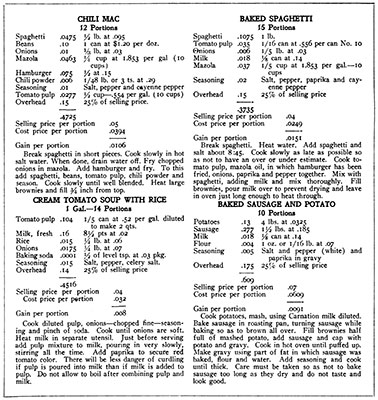

The major problem was how to produce a

predictable quantity and uniform quality of food. When Pope found

there was no practical system of recipes available, he

converted his wife’s New England recipes to commercial formulas. He

worked out a series of menus and recipes that produced a given

number of servings from a given set of ingredients. Perhaps more

significantly, the preparation could be handled by employees with no

food service experience.

Harry Pope liked St. Louis and decided to stay. Within 10 years, the International Shoe Company kitchens were serving 15,000 meals a day. Pope, who became personnel manager of the company, was a recognized authority in the restaurant industry. In 1929, he was elected president of the International Food Service Executives Association.

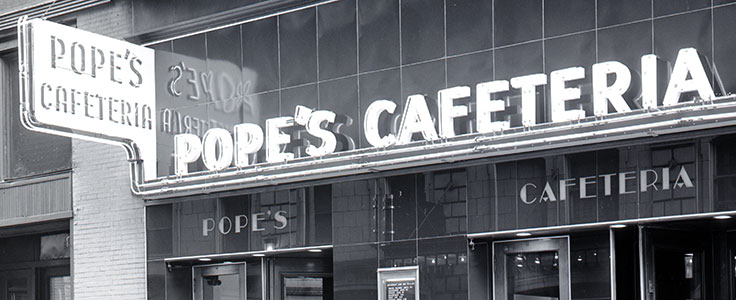

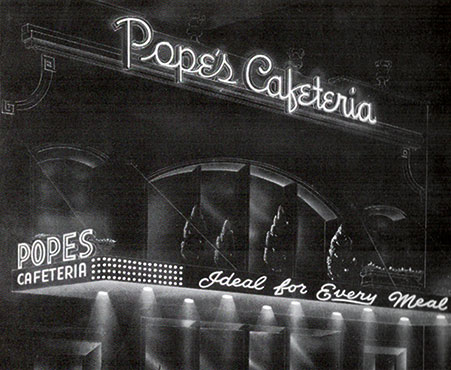

In 1933, Pope was offered the YWCA cafeteria at

3538 Washington Avenue. He backed his sons, Edwin and Harry Howland Pope,

who opened the first Pope's Cafeteria at the site.

In 1936, Pope acquired the

Child’s Restaurant at 804 Washington, which became the second Pope's

Cafeteria. He then resigned from

International Shoe to join his sons on a full-time basis.

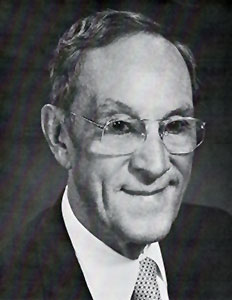

Edwin Pope was educated at Cornell University's School of Hotel and Restaurant Management. He was company president from 1936 to 1948.

Harry H. Pope, born in St. Louis in 1914,

abandoned a college career after high school because of the

Depression. He received his degree in business administration from

Washington University at the age of 33.

The recipes Harry

Pope devised for the International Shoe Company became the basis for

the Pope's Cafeteria operation. Three major ingredients went into Pope’s

system – formulated recipes, careful training and strict adherence

to policy – and none was foremost or more important than another.

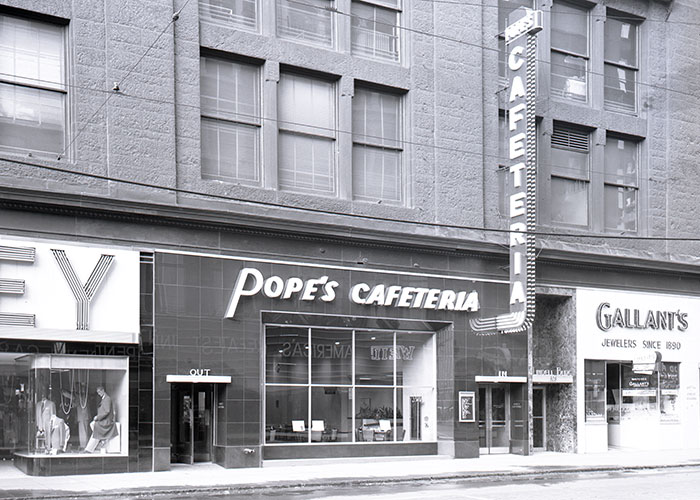

Pope's two downtown cafeterias acquired a loyal following among shoppers and downtown workers who breakfasted, lunched and sometimes supped there. For their regulars, the cafeterias, with their cavernous dining rooms dotted with Formica tables and their cadre of polite, smiling waitresses, became a second home.

Pope’s was the kind of

place where customers and employees grew old together, where

friends gathered or were made, where romances began and ended – amid

subdued prints, potted plants, soft lighting and dignified columns.

Mildred Hoppe, director of food production for

Pope's Cafeterias, was instrumental in designing Pope's recipes.

Pope's prize-winning

nut torte, made with graham cracker crumbs and nuts folded into

a meringue-type base, was Hoppe's creation.

In 1942, Harry Pope re-entered the factory food service field by obtaining the contract to feed the workers of the Amertorp Torpedo plant at 3200 South Kingshighway. Eventually, Pope's would expand its factory and contract food service to more than 15 companies.

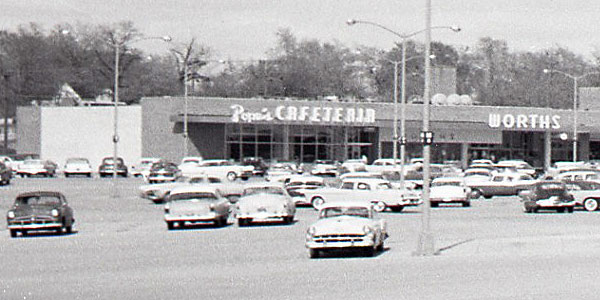

In 1957, Pope’s opened

St. Louis' first suburban shopping center cafeteria in the Northland

Shopping Center.

In November of 1958, the upscale Pope's Self Service Restaurant opened in the Siteman Office Building in Clayton. The restaurant was designed after a plan of service which was discovered by Pope during a trip to Europe. In this plan, orders for hot food were placed with the cashier and served directly by the chef from the kitchen.

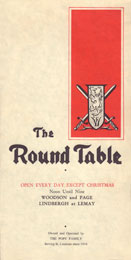

Pope's continued to expand into suburbia, with Pope's Cafeterias in the Westroads and South County Shopping Centers. By 1964, there were six Pope's Cafeterias, with another downtown cafeteria at Seventh & Pine on the way. In the spring of 1964, Pope's took over operation of the Golden Falcon Cafeteria and The Round Table Restaurant in the Town and Country Mall at Page and Woodson. The two restaurants had opened in 1962 and had originally been operated by The Round Table Restaurateurs, a corporation whose president was Arthur M. Donnelly, publisher of weekly newspapers in St. Louis and St. Charles counties. The exterior of The Round Table had an Old English architectural design. A canopied entrance extended to the parking lot. Interior decor had medieval motifs, with Old World chestnut woods, lava stone wall treatments, stained-glass windows of heraldic design and beamed ceilings.

The Round Table featured an open-hearth fire. A cocktail

lounge called The Sword and Anvil Tavern, which also served

food, adjoined the restaurant. By 1967, Pope’s provided more than 30,000 meals a day in the St. Louis area and had more than 700 employees. Its South County Shopping Center location was the most profitable single cafeteria in the country. The company's operations continued to draw on the food service preparation and management system techniques developed by Harry Pope. Their restaurants and cafeterias became showpieces for Europeans who wanted to learn how to run a restaurant without experienced help.

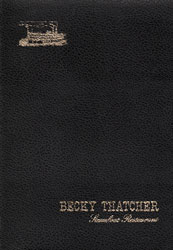

In 1969, Pope's opened a restaurant on the

Becky Thatcher, a stern-wheel steamboat on the St. Louis

riverfront. With the historic Eads Bridge in the background,

visitors crossed a gangplank, ascended winding stairs and entered

through stained-glass doors.

The main salon, which seated 100 guests, had

white walls accentuated by gold trim. Marble-topped tables of white

and gold were complemented by black captain's chairs covered in red

leather with brass studs. A lounge section seating 70 persons was on

the bow of the ship. Another dining room seating 70 was on the upper

deck.

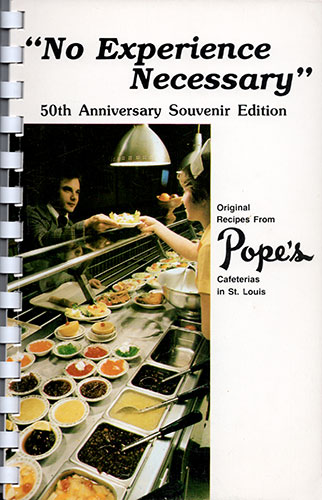

The evening menu was

limited to three entrees associated with riverboat dining – channel

catfish, steak and southern fried chicken. These items were repeated

on the luncheon menu, with expanded offerings including sandwiches

and salads. Pope's steamboat restaurant was short-lived. It was sold to the Great River Steamboat Company in 1970. In 1975, the Becky Thatcher was moved to Marietta, Ohio. Pope's continued to expand throughout the metropolitan area. Cafeterias were opened in West County Center and Northwest Plaza. Three Holloway House cafeterias were acquired. Three Briefeater quick food restaurants, featuring a full line of pastries, salads, soups and sandwiches, were open – two downtown and one in Clayton. The El Rancho, a self-service restaurant featuring Mexican food, was opened downtown in the Famous-Barr garage building. By the end of 1972, Pope's holdings included eleven public cafeterias, four Round Table Restaurants, two Seven Kitchens Restaurants, three Briefeaters, three retirement residence food services and ten food services in factories or office building. Harry A. Pope continued to work five days a week, even after officially retiring to a consultant basis in August of 1972. He visited all units on a regular basis to make sure his recipes and policies were being followed. In 1979, Pope's published a cookbook with some of its favorite recipes. An expanded 50th Anniversary Souvenir Edition was published in 1983.

Eventually, tastes changed. Fast food and takeout hurt cafeteria-style restaurants. The big factories where Pope's got its start began fading away. On September 1, 1971, Food Management Systems acquired the original Pope’s Cafeteria at 3538 Washington. The name of the cafeteria was changed to Hasty House Cafeteria. After 44 years, on June 27, 1980, the Pope's Cafeteria at 804 Washington Avenue closed its doors for the last time. Almost 8,000 meals per day were served during the cafeteria's all-day schedule in the 1940s, '50s and '60s. But by the 1970s, the crowds had dwindled. The cafeteria was the last of five Pope-run restaurants downtown. On December 9, 1984, Harry A. Pope died in his sleep at his home in Clayton at the age of 97.

In 1989, the last Pope's location in Florissant

closed. Pope’s Cafeterias died along with the leisurely lunch.

Copyright © 2023 LostTables.com |