|

Richard Perry Richard Perry's parents were both from the same farming community in Potomac, Illinois. After they were married, they moved to Chicago, where Perry was born. When his father was drafted in World War II, Perry and his mother returned to the family farm, where they stayed until the war ended. It was on the farm that Perry developed some basic attitudes about food. There was no electricity or running water. Cooking was done on a wood burning stove. Breakfast was hearty and lunch was the major meal of the day. "On the farm, I used to help with the butchering," Perry recalled. "I can remember my grandfather seasoning sausage in the smokehouse and frying off bits to taste until it was just right. The icehouse had an artesian well that was almost as cold as ice. Mother would keep the freshly churned butter and other dairy products in crocks submerged in the icy water, while other things that needed to be refrigerated would stay cool in that dark room. "That cave was our refuge when tornadoes threatened, but it also was the larder for untold numbers of seasonal goods that were 'put up' - tomatoes, beans, corn relishes, jams and preserves, and mincemeat - they were all there. "I remember my aunt's potato salad, fresh peach pies, dark chocolate cakes with fluffy white icing, and home cured bacon with fried eggs." Perry's family moved to St. Louis in 1948; he grew up in the St. Louis Hills neighborhood. He attended Cleveland High School and was a student at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana when he was drafted. After two years in the Army, Perry returned to Champaign to earn an undergraduate degree in history, mathematics and German. He graduated in 1964, and went to work for the national college social fraternity, Delta Sigma Phi. After two years, he quit and moved to Chicago to work for McGraw Hill, the textbook publisher. During the five years Perry was working for McGraw Hill, the idea of opening a restaurant was simmering in his mind. "As I traveled through my territory, I ate out a lot, and every restaurant had either continental cuisine or steak," Perry recalled. "I remember wondering often why no nice restaurants were serving the good food I remembered from the farm in Potomac."

As the bottom dropped out of the textbook

market, opening a restaurant became more appealing. But Chicago was too expensive. One summer weekend, Perry was visiting friends in St. Louis. While driving, he noticed an old house on the northwest corner of Jefferson and Utah, with the windows boarded up. At City Hall, he learned the name of the owner, a woman in Greenville, Illinois, whose family had built the house. When Perry called her, she said she would sell the building for $10,000.

"I drove to Greenville with a wad of hundred

dollar bills in my pocket," Perry remembered. "I reminded the woman

that there was no electricity, no gas, no furnace and no running

water in the building. I told her I would give her $2,700 in cash." Perry resigned from his job at McGraw Hill and moved to St. Louis. He began renovating his new building at 3265 South Jefferson Avenue, living above his would-be restaurant.

In the winter of 1972,

after the renovation had taken twice as long and cost twice as much as

planned, Richard Perry opened the Jefferson Avenue Boarding House. The Jefferson Avenue Boarding House had no sign. The dining room had a high ceiling, with walls painted a light mustard color above a Williamsburg flowered print wallpaper. Greenery, along with antique pitchers and glasses, were on the window sills. The walls were adorned with prints and a bas-relief. An old clock with a pendulum ticked on the south wall. The linens were crisp and white, with large napkins rolled into tight U-shapes expanding from stemmed water glasses. Fresh flowers were on every table, budding from bulbous green Perrier water bottles. When it opened, the Boarding House seated only 40 for dinner.

Perry was the maître d', the waiter, the

cashier and the voice on the phone taking reservations. He and the bus boys wore blue denim work

shirts and jeans, with white aprons. Soup was ladled from a

blackened kettle and coffee was poured from an old-fashioned blue

enameled pot.

There was a fixed menu each night - diners ate what was served to them, as they would at a boarding house. Since Perry had no restaurant experience, a single menu was all he and his staff could handle. "I opened serving one meal a night, but a different meal every night. I did that because that was all I could do," Perry recalled. The menus, based on recipes from turn-of-the-century St. Louis hotels, restaurants, riverboats and private homes, were usually available a day or two in advance. "It all depends on what's at the market," Perry explained at the time. "We only work with fresh meat and vegetables, so it's hard to know too far in advance." In 1972, a typical dinner was tomato soup, braised cube steaks, boiled new potatoes, cauliflower, salad and chocolate cake for dessert - all for the price of $4.50. By 1977, The Boarding House was serving dinner on two floors; the main dining room was upstairs, with a smaller room downstairs designated for private parties. Dark chocolate colored walls replaced the mustard colored walls and print wallpaper. There were now two seatings at dinner - three on Saturdays - and breakfast was served at 12:30 on Sundays.

Dinner prices had risen to the range of $10 per

person. Prices varied slightly from day to day, depending on the

entree being served. The menu was chosen for an entire month, and

was mailed to interested customers for a charge of $2 per year.

Starting in 1978, the Boarding House entree no longer changed nightly, but weekly. Three-month menus were mailed

out to interested customers at no charge.

By 1980, the Jefferson Avenue Boarding House was offering a choice of entrees each evening; there was still no menu. A waiter described the three or four entrees of the day, which were served with a salad and potato or vegetable. The salad was offered before or after the entree. Appetizers and dessert were extra. A full dinner was now $15-$20 per person, not including wine.

On January 19, 1982, a long black awning went

up over the doorway of the the restaurant at 3265 South Jefferson

Avenue. On its 10th anniversary, the Jefferson Avenue Boarding House

became simply Richard Perry.

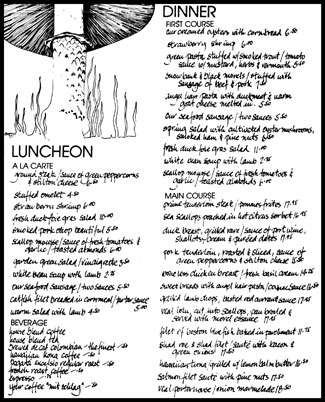

Along with the new name were new dinner,

brunch, luncheon and dessert menus. The dining room with

its white linen, U-shaped napkins, fresh flowers in green Perrier

bottles and chocolate background stayed the same.

When Perry opened the Jefferson Avenue Boarding House, he was already thinking in terms of American cuisine, reproducing the best of St. Louis menus of the past and serving in boarding house manner. Although the name of the restaurant and the cooking style had changed, the thrust was still toward American food. "Our sauces aren't as heavy anymore, but they are based on some of the same recipes we've always used," Perry said. He and his young chef, Gregg Mosberger, emphasized local, seasonal foods as much as possible on their menus. "That's the way restaurants will be going in the next 10 years," Perry predicted.

The menus changed almost weekly, according to

what Perry and Mosberger found at the local produce markets. On the

theory that the best food never came into the market, they found

local sources, especially for fish. "It's a shame to have to rely on

the East Coast swordfish and scrod when there is bluegill and trout

here in Missouri," Perry said.

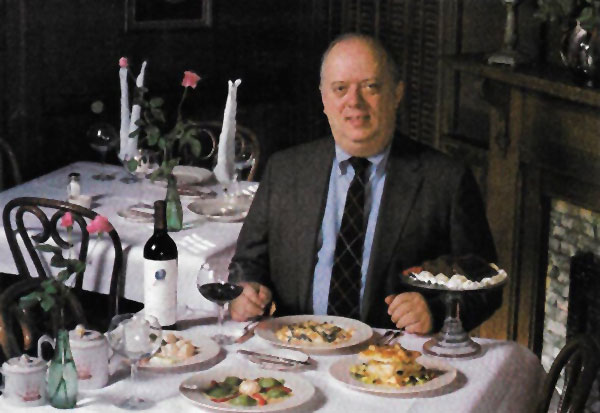

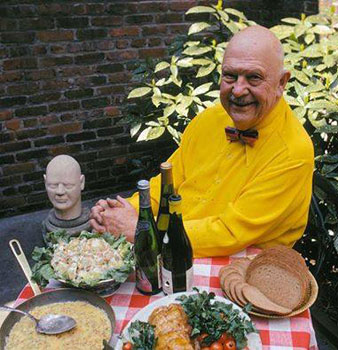

Perry's menus included dishes like pork tenderloin served with port sauce, enriched with Iowa Maytag Blue cheese. Boneless breast of chicken was occasionally braised with smoked country ham and appeared in a sauce of cream and wild mushrooms. At other times chicken breasts might be rolled around green onions, lightly breaded and accompanied by tarragon creams. Local fish, such as smallmouth bass and bluegill fillets, were staples of the Perry kitchen. Even vegetables took on a regional slant; there might be wild Illinois asparagus wrapped in Missouri's Boone County ham. According to Perry, Midwesterners had a special affection for sweets, and his desserts mirrored that. Baked hazelnut meringue, layered with semisweet chocolate and raspberry buttercream with raspberries on top, was a specialty of the house. Fresh gooseberry pies, rhubarb Bavarian cream, pecan tarts and old-fashioned chocolate pudding with maple cream were among other delights. The restaurant had a new garden in back for outdoor dining. White patio furniture sat on a brick floor surrounded with flower beds. Fountains gurgled at both ends of the garden, and overhead netting shaded diners. "To take advantage of the weather, we recently added an outdoor summer garden, with its own all-cold menu," Perry expounded. "Fresh herbs grow around the border, and are collected daily for seasoning. Customers there are encouraged to order several different dishes for the table, with everyone getting a little taste of everything."

Perry and Mosberger's new

cold menu included a raw vegetable plate, an assorted cold meat

platter served with three mayonnaises, fresh fruit with strawberry

bread and cream cheese, ceviche of bay scallops, pates, and shrimp

and avocado salad. Perry said he had changed the name of his restaurant in part to gain attention for the restaurant. But the food didn't change, because Perry liked it the way it was. He called the food Midwestern. "What I call Midwestern food really stretches from western New York all the way to the West Coast. When you think about it, the food that they're cooking as the new California cuisine is Midwestern food. They're serving chicken and noodles and pretending it's a new dish. Just because they're making fresh egg noodles and using range-fed chicken doesn't make it any different from what I remember as a kid." Richard Perry became known as a landmark restaurant with a national reputation for creative and imaginative dishes that retained the flavors of America's heartland. Perry was quoted on the subject of American cuisine by food writers around the country.

"I make the point that it's really the

restaurants that failed American food. The restaurants that existed

from the '30s, '40s, '50s and '60s. They were trying to present

highfalutin food, and all they could present was some kind of

continental thing. I think good American food has always been

around, but it's been preserved in the homes, primarily in the rural

homes of the Midwest and South."

Perry resisted ceremony. "I don't want to be stiff and formal. That's why we don't put our people in tuxedos, although we often talk about it.

"I think St. Louisans have been bamboozled into

thinking that service is equated with somebody standing at the table

tossing pasta in a flaming chafing dish. In my mind, that's how you

ruin the pasta by overcooking it. I think there's another thing some

people are hung up on. It's good if it's hot. I agree with (James)

Beard that food tastes better if it's closer to room temperature." "I'd been looking to move downtown for some time, and then this opportunity came along and I took it," Perry explained. "The volume of our business has picked up dramatically, and I think we're more accessible to people now. "Instead of serving lunch and dinner and a brunch on the weekend, I'm now serving breakfast beginning at 6:30 and dinner until midnight. But I'm proud to say I don't think our quality has slipped. We've maintained our quality food and our good service, but that's not to say that we don't make our share of mistakes, as well." St. Louis Post-Dispatch food critic Joe Pollack, who had sung Perry's praises since he opened his restaurant in 1972, disagreed. In a December 28, 1989 review, Pollack lamented:

Perry had signed a two-year contract with the Hotel Majestic, and was there until the end of 1989. When he left the hotel, he reopened in his original location, naming it the Jefferson Avenue Bistro. "I stuck with the same food but encouraged customers to order for the whole table, like you do with tapas," Perry said. "Customers didn't want to do that. I guess I was ahead of my time." Perry closed the restaurant on the last day of 1990. But the restaurant business was in his blood.

Richard Perry said that his chief thrill in life was going out to eat. "You sit there and you pick it apart and have all kinds of fun. Nothing better." On Christmas Day 2017, the restaurateur and chef who was at the forefront of the Modern American food movement stopped having fun. But his legacy lives on. Copyright © 2018 LostTables.com |

|||||||||||||||||||||