|

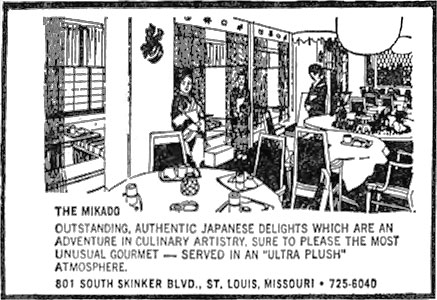

The Mikado

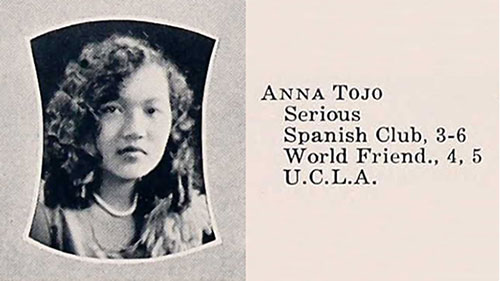

Anna Tojo was born in Modesto, California in

1913. Her parents had immigrated to the United States from Japan.

She grew up in Los Angeles, graduated from

Hollywood High School in 1930 and attended UCLA for two years.

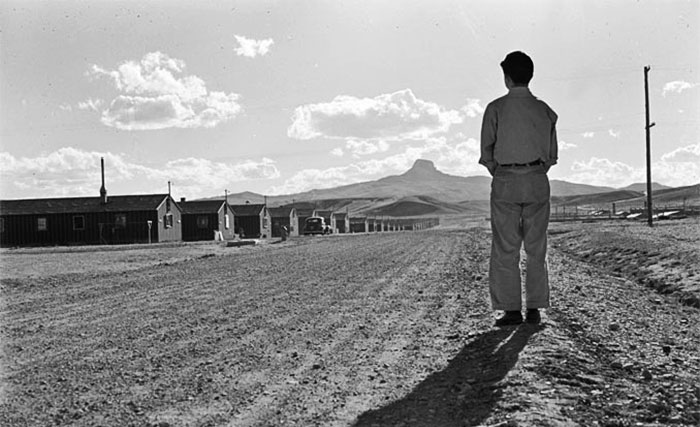

Hiroaki Shigemura was born in Seattle, Washington in 1906. His parents had also immigrated to the United States from Japan. On May 8, 1935, the Santa Ana Register recorded that Hiroaki Shigemura, age 28, and Anna Tojo, age 21, had applied for a marriage license in Los Angeles. Hiroaki and Anna Shigemura lived at 1119 Hover Street in Los Angeles. Hiroaki worked as a clerk in a fruit stand. They had two children; Lydia was born in May of 1941 and Ronald was born in May of 1942. On the morning of December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. On August 12, 1942, the Shigemuras and their two children entered the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Heart Mountain, Wyoming. The Heart Mountain Relocation Center was one of ten concentration camps used for the internment of Japanese Americans evicted from the West Coast during World War II. When the camp was at its largest, it held more than 10,000 people, making it the third largest town in the state.

The Heart Mountain facility was surrounded by

barbed wire, sentry towers and armed guards. It consisted of 450

barracks, each containing six apartments. The largest apartments

were single rooms measuring 24 feet by 20 feet. None had

bathrooms. Internees used shared latrines. None of the apartments

had kitchens. The residents ate their meals in mess halls.

Anna Shigemura was pregnant when she arrived at Heart Mountain. In March of 1943, she gave birth to her third child, Joyce Shigemura, while interned at the facility. By January of 1945, the order banning Japanese Americans from the West Coast had been lifted. The government encouraged internees to leave the camps for the interior of the United States to "take advantage of educational and employment opportunities." The director of the War Relocation Authority told inmates that "the dense congregation of Japanese in vital Coast defense areas" was one reason for their exile and incarceration. "The ultimate solution of the entire problem," he argued, "lies in getting the people of Japanese descent resettled throughout the nation."

When Anna Shigemura and her family were

released from Heart Mountain, they no longer had a home to return to

in Los Angeles. So they traveled to "the

interior of the United States" and resettled in Cincinnati.

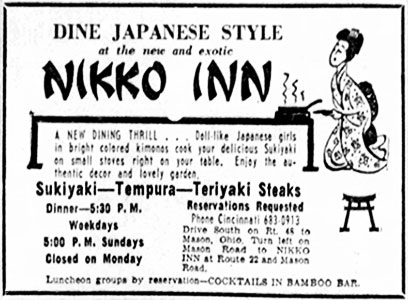

The Shigemuras setup home in the Cincinnati neighborhood of Avondale. In short order, they added three more members to their family; Edward was born in 1947, Donald in 1950 and Cathy in 1952. Hiroaki was employed at Golden Rule Electric. Anna sponsored Cincinnati's Japanese Wives Association, an organization of Japanese women who had married American servicemen. But Anna Shigemura was not content to be a stay at home mom. So she became a restaurateur. * * * * * On March 24, 1962, the following appeared in the Cincinnati Enquirer.

Nelson S. Knaggs, a prominent explorer and world traveler, was chairman of the board of the Nikko Inn. His wife, a Cincinnati socialite, was the restaurant's president. And Anna Shigemura was the Nikko Inn's heart and soul. Anna Shigemura managed the 100-year-old farmhouse turned restaurant, with its bright Japanese lanterns, red Torii gate, Japanese garden surrounded by a high bamboo fence, and lacquered front door. Anna Shigemura supervised the kimono clad doll-like Japanese hostess perhaps recruited from the Japanese Wives Association she sponsored who seated patrons on soft cushions at low tables, after they had removed their shoes. Anna Shigemura offered unique cocktails from the Nikko Inn's Bamboo Bar, including the Typhoon, Jiu-Jitsu and Pearl Diver. Anna Shigemura recommended dishes from the Nikko Inn's large red menu. Entrees included sukiyaki, tempura, teriyaki and Genghis Khan, all served with Japanese hors doeuvres, soybean soup, marinated cucumbers, steamed rice and green tea. Anna Shigemura

watched her hostesses prepare food on small stoves at each table and

helped first time diners use chopsticks.

Anna Shigemura helped celebrate the Nikko Inn's fourth birthday in the spring of 1966. She was still managing the restaurant in November of 1966. But then something happened. Something happened that caused Anna Shigemura to leave the Nikko Inn. Something happened that caused her to leave her husband and her children. Something happened that caused her to leave Cincinnati. By early 1967, Anna Shigemura was living in St. Louis and Hiroaki Shigemura was the manager of the Nikko Inn. * * * * *

In 1959, plans were announced for a luxury

17-story cooperative apartment building on the southwest corner of

Skinker Boulevard and Southwood Avenue in St. Louis County, opposite Forest Park. The

801 Skinker Building was completed in 1962 and had space for a

restaurant on its mezzanine. Its first occupant was the Carrie Blayney Restaurant, a spinoff of the Carrie Blayney Catering Service

which had been in existence since 1936.

Better at catering than running a restaurant, Carrie Blayney vacated the space in less than a year. In October of 1963, Ted and Alvine Kubatsky followed with their Eight-O-One Restaurant.

"Ted and I really dont have to be there at

all, our staff is so wonderful," Mrs. Kubatsky declared. Theodore Kubatzky filed for bankruptcy in March of

1966. After the Kubatsky's restaurant closed, the space on the mezzanine of the 801 Sinker Building sat empty. * * * * * When Anna Shigemura relocated to St. Louis, she moved into a unit in the Montclair Apartment Building at 18 South Kingshighway. And then she did what she was good at. She opened a Japanese restaurant. On February 7th and 8th of 1967, Gilbert and Sullivan's opera The Mikado played at the American Theater in St. Louis. Perhaps Anna Shigemura knew of this production. Perhaps she attended one of the performances.

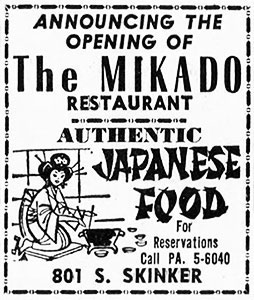

In any event, on February 10, 1967,

Anna Shigemura filed a form with the state of Missouri incorporating

a business with the name "The Mikado, Inc." And in March of 1967,

The Mikado restaurant opened in the mezzanine space of the 801

Sinker Building.

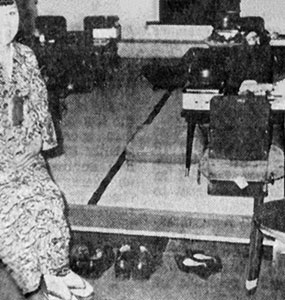

The Mikado flew under the radar with the critics for its first four years in business. But Anna Shigemura had no trouble drawing customers. She had successfully replicated the Nikko Inn, with a similar ambiance and similar menu. Her hostesses were all Japanese war brides, perhaps wives of soldiers stationed at Scott Air Force Base. Her red menu offered sukiyaki, tempura, teriyaki and Genghis Khan, just as it had in Cincinnati. Her specialty drinks even included the Nikko Inn's unique Typhoon and Jiu-Jitsu cocktails.

The Mikado was so successful at 801 South

Skinker that Anna Shigemura needed more room. She watched from her

unit in the Montclair Apartment Building as a succession of

restaurants moved in and out of the former Frontier Room space,

first the Montclair Room and then Carlos Restaurant. Undeterred,

she signed a 10-year lease, and in May of 1971, moved The Mikado to

18 South Kingshighway.

After graduating Sycamore High School in Cincinnati in 1970, Cathy Shigemura moved to St. Louis to live with her mother. Charles Sherman mentioned her in his September 13, 1971 St. Louis Post-Dispatch review, written for an audience still unfamiliar with Japanese food and culture.

* * * * * Ralph and Helen Pirman were married in Louisville, Kentucky on September 9, 1939. They lived in Fort Thomas, Kentucky. Ralph Pirman worked across the Ohio River in Cincinnati. Hiroaki Shigemura died in Cincinnati on November 20, 1970. His obituary stated he was the beloved husband of Anna Tojo Shigmura. Helen Pirman died in Cincinnati on March 18, 1972 after a long illness. According to her obituary, she was survived by her husband, Ralph H. Pirman. Anna T Shigemura and Ralph Howard Pirman filed for a marriage license in the City of St. Louis on May 1, 1972. * * * * * The Mikado continued to thrive at its South Kingshigway location. St. Louis Post-Dispatch food critic, Joe Pollack, penned glowing reviews in 1974 and 1976. He was particularly fond of the tempura.

On May 2, 1977, Ralph Pirman died at the age of 59. Perhaps related or perhaps not, Anna Pirman failed to negotiate a new lease for her restaurant in the Montclair Apartment Building. She closed The Mikado in the spring of 1982. * * * * * Anna Pirman lived the rest of her life in St. Louis. There's no evidence she ever returned to Los Angeles or Heart Mountain or Cincinnati. The Mama San of The Mikado died on August 28, 2001. She was cremated and placed alongside Ralph Pirman at Valhalla Cemetery in St. Louis County.

Copyright © 2022

LostTables.com |