|

Chez Louis / Bernard's

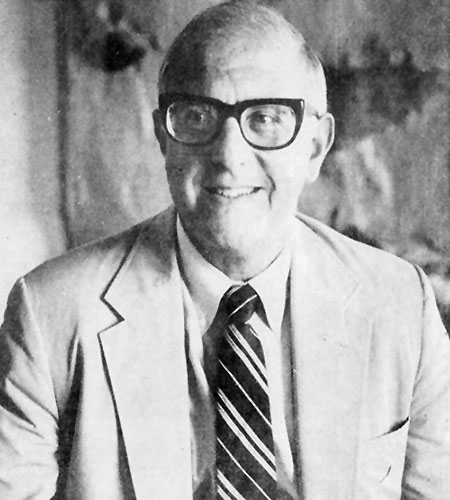

Morton Louis Meyer was born in St. Louis on

January 25, 1931. After graduating from Princeton University in

1952, he served in the army during the Korean War.

Because of his fluency in several languages,

Meyer was sent to the U.S. Army language school in California, where

he scored the highest mark ever on the school's exam. He was shipped

to Germany for training and then to eastern France as a

counter-intelligence agent. While in France, Meyer developed a love

for travel, art and French food.

On June 14, 1954, while still in the service,

Meyer married Roxanne Harris of Highland Park, Illinois. They would

have three children ― Nancy, Danny and Tommy.

Danny Meyer went on to become a renown New York

restaurateur. In his autobiographical book, Setting the Table,

Danny looked back at his father's life from an adult perspective.

My parents, Roxanne

and Morton Louis Meyer, had spent the first two years of their

youthful marriage in the early 1950s living in the city of

Nancy, capital of the French province of Lorraine, where my dad

was posted as an army intelligence officer.

In 1955, at the conclusion of my

dadís overseas military service, my parents were still very much

in love with each other and with Europe. Their knowledge of and

fondness for France in particular was a powerful bond between

them. In St.

Louis my father parlayed his love of all things French into a

career as an innovative and successful travel agent.

Meyer joined the William H. Goldman Travel

Agency, which was started by Goldman in 1919. In 1956, the agency

was incorporated as the Goldman-Meyer Travel Agency, with Meyer as

secretary-treasurer. When Goldman retired in 1958, Meyer became

president of the firm. Meyer's brother, Richard, would become vice

president.

|

|

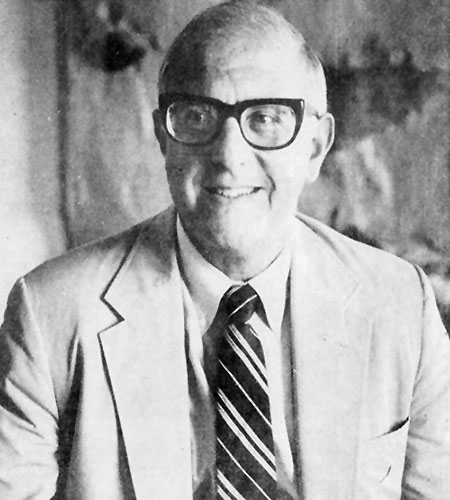

Morton

& Roxanne Meyer

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Dec 9, 1958 |

Morton

Meyer

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb 27, 1959 |

In 1960, as large commercial jets began

transporting Americans overseas, Morton Meyer developed Open Road

Tours.

His agency, Open Road

Tours, packaged customized driving trips, often in conjunction

with Relais de Campagne, a network of lovely family-operated

inns around France. This was long before such excursions off the

beaten path became common in the travel industry. Dad exulted in

planning these driving tours of the countryside; heíd note

exactly where travelers would stumble upon a certain vineyard, a

worthwhile museum or a particularly good bistro. His clients

loved his attention to detail; his business thrived.

Meyer's love for Europe extended into his home,

enveloping Danny and his siblings.

At home, too, he and

my mom were Eurocentric. They often hosted cocktail parties and

dinner parties for friends and business colleagues from France,

Italy and Denmark, who either were in town on business or had

made a detour to St. Louis just to see us. For several years our

house was home to the grown children of French innkeepers. By

day these young people would help out in Dadís office with

translations and administrative tasks, and by night they would

act as au pairs for my sister, Nancy, my brother, Tommy, and me.

French was always being spoken around

the house, either by our guests or by my parents (who used it at

the dinner table especially when they wanted to discuss

something not meant for our ears). Our neurotic, inbred French

poodle, Ratatouille, was named after my dadís favorite Provencal

dish.

Meyer lived life to the fullest, with a

propensity for risk taking.

My father was

unquestionably my childhood hero: a hedonist, a gastronome and a

man who cherished and passionately savored life. He loved the

excitement and risk of the racetrack and gave me a taste for it,

even when I was too young to place bets legally.

Dad also took risks as a businessman.

He was always coming up with exciting new ideas based on his

love of travel and food, and on his constant drive to share his

finds with others. At one point Open Road Tours had offices and

staffs in Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, and Paris. Later, it

opened offices all over Europe.

But disagreements between Open Road's inside

and outside investors, and suits filed by the Hertz Corporation seeking

to collect money they were owed, forced Open Road to file for

bankruptcy.

I never fully

understood how or why, but sometime in the late 1960s, when I

was still a young boy, Open Road Tours went bankrupt. I remember

abundant tears and shame, but few details. I heard comments

like, "We expanded too quickly."

My paternal grandparents were torn

apart too. Their only two sons had been in business together ―

my father as president and his younger brother as vice

president. Whatever events had led to the bankruptcy had also

driven a sharp wedge between the two brothers.

My mother was anguished, and her

disappointment and disapproval were apparent. Business details

were not openly discussed, but the familyís bruises were deeply

felt.

Undeterred, Meyer switched from the travel

business to managing hotels in Italy.

In 1970, when I was

twelve, my father leaped into the hotel business in Italy.

Despite the pleas of my mother, and with her father's begrudging

help in the form of a $1 million loan, he committed himself to

long leases on one hotel in Rome and another in Milan. He was

certain that becoming a hotelier would be his ticket to fortune.

My mom maintained that it promised

nothing more than protracted absences from home. There was

always some reason my dad had to go to Italy. Each time the

hotel workers went on strike, he flew to Rome or Milan to help

make beds. Business flagged and lagged, and although he was

spending half a month at a time away from his family to address

problems, it inevitably proved impossible for him to operate a

hotel business across two continents. At an enormous financial

cost and an even greater emotional cost, my father finally found

a buyer for his two leases. He then went on to his next idea.

While in Italy, Meyer noticed that most Italian

hotels operated at an 80-percent occupancy rate between Easter and

November 1st, and at a 20-percent occupancy rate the rest of the

year. The discrepancy disturbed him and he became determined to find

a way to lure travelers in the off-season.

In 1972, still

irrepressibly optimistic, my father created another new

business, called Caesar Associates. This new company would sell

packaged group tours at a deep discount for a very narrow niche

of travelers known as interliners ― airline employees and their

families. Interliners could fly standby at unbelievably low

rates. Dadís business model was simple but original. He

aggregated all the discounts to which interliners were entitled

and packaged trips lasting up to two weeks.

In addition to low airfares, he

negotiated rock-bottom rates for hotels, ground transport,

sightseeing, shopping and dining. The value he added was to

offer highly imaginative itineraries and use the underlying

buying power of group travel to create an extraordinary rapport

between price and quality. He hired sparkling young tour guides

at each destination, and he kept his clients informed of travel

opportunities by writing an endless stream of marketing

collaterals.

Caesar Associates actually thrived for many years, with outposts

in London, Paris, Copenhagen, Madrid, and Rome. But this success

wasnít enough for my father. Having failed to learn some

critical lessons from his earlier business failures in the 1960s

and 1970s, he gambled the fortunes of his entire business on

another new one, involving risky and questionable real estate

and hotel deals back in St. Louis.

|

|

|

Danny Meyer |

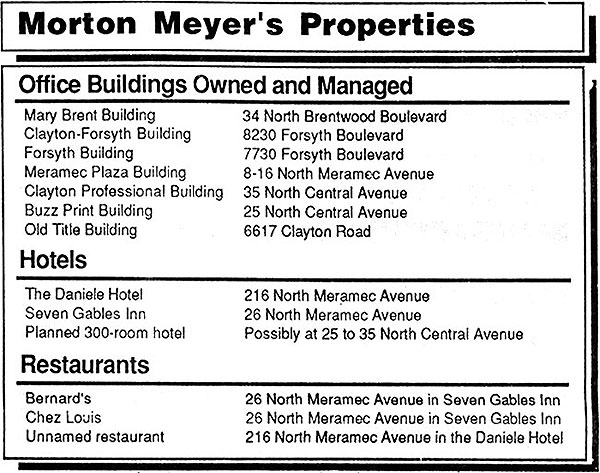

Morton Meyer entered the Clayton real estate

market in 1977

when a banker friend suggested he needed to shelter

earnings from his travel business. His initial purchase was the

Mortgage Building at 7730 Forsyth.

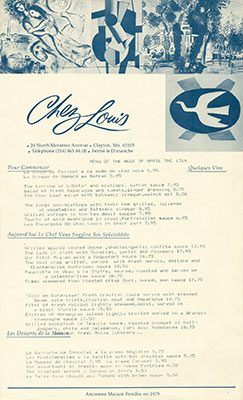

In October of 1979, Meyer plunged into the

restaurant business. He opened Chez Louis at 26 North Meramec in

Clayton. The storefront space in the 53-year-old Seven Gables

Apartment Building had previously housed the Clayton Coffee Company.

Meyer owned Chez Louis with Bernard Douteau, who served as

the restaurant's chef and general manager. Douteau, born

in a small town south of the Loire Valley, had worked as a hotelier

in France, as will as in Ethiopia and Italy. In Italy he managed two

hotels for Meyer, whom he had met five years earlier in Paris.

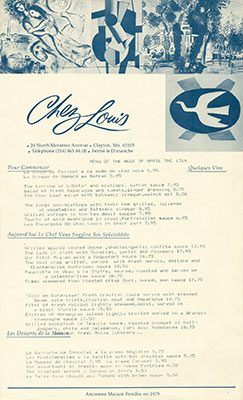

Chez Louis featured white tablecloths with

pastel napkins, heavy service plates and handwritten menus. Colorful prints and posters punctuated white plaster

walls.

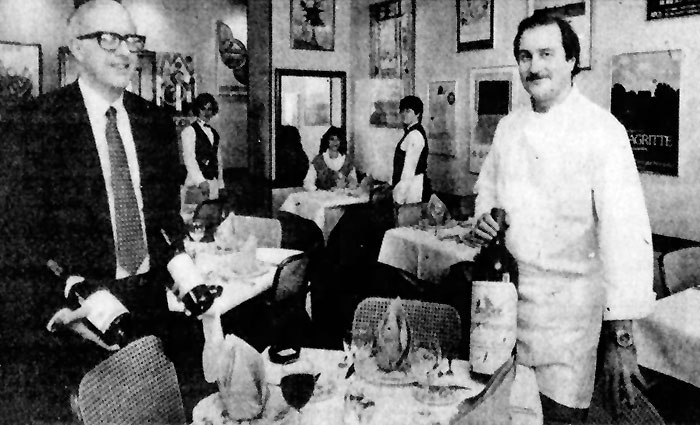

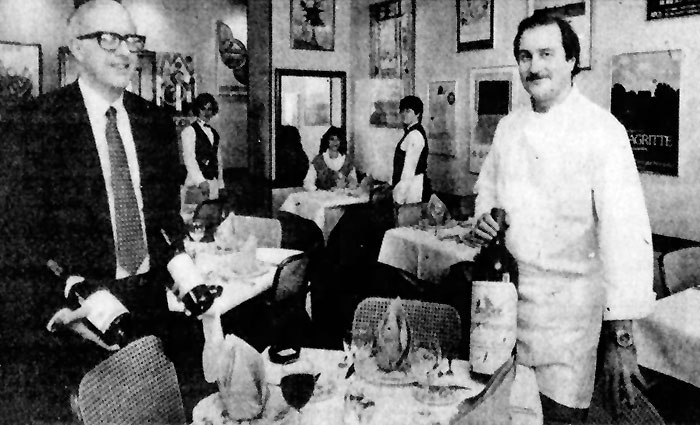

|

Morton

Meyer (left) and Bernard Douteau at Chez Louis

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Nov 22, 1984 |

Chez Louis' menu was small and changed

frequently. Restaurant critic Joe Pollack provided an

overview of

the cuisine in his March 25, 1982 St. Louis

Post-Dispatch review.

The Chez Louis

cuisine style is French, kind of a happy compromise between the

truly haute cuisine, which can be overwhelmingly rich, and the

truly nouvelle, in which a food processor grinds everything into

the texture and taste of baby food. Sauces are light, with a

beautifully modulated touch of herbs and spices and a base that

involves the reduced stock of the meat or fish. Vegetables are

cooked quickly to retain color and flavor.

And then there's the presentation,

which is glorious. Each morsel is perfectly arranged on the

plate, colors are right and the feeling can be that the dish is

too pretty to eat Ė until the first whiff of savory herbs

tingles the palate and stimulates the salivary glands.

|

|

1984

Chez Louis Menu

(click image to enlarge) |

Chez

Louis Interior

|

In November of 1982, Meyer and Douteau opened a

second restaurant which they named Bernard's. It was located

adjacent to Chez Louis, in the 18 North Meramec space of the Seven

Gables Apartment Building.

|

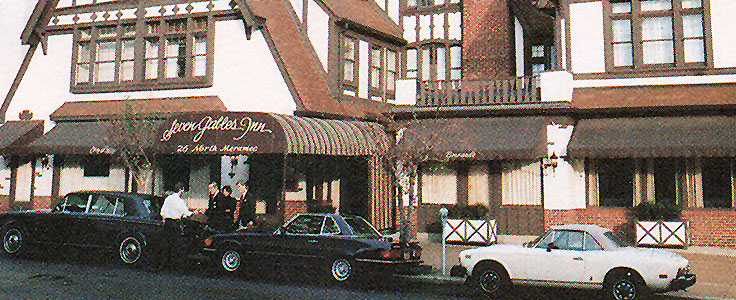

| Chez

Louis and Bernard's, Seven Gables Apartment Building,

circa 1983 |

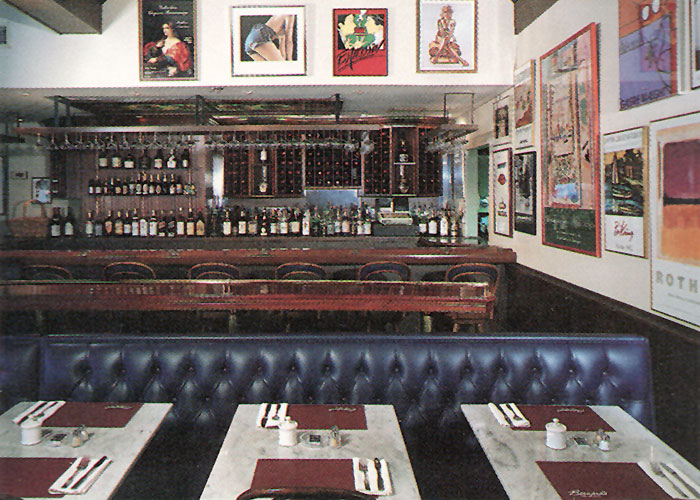

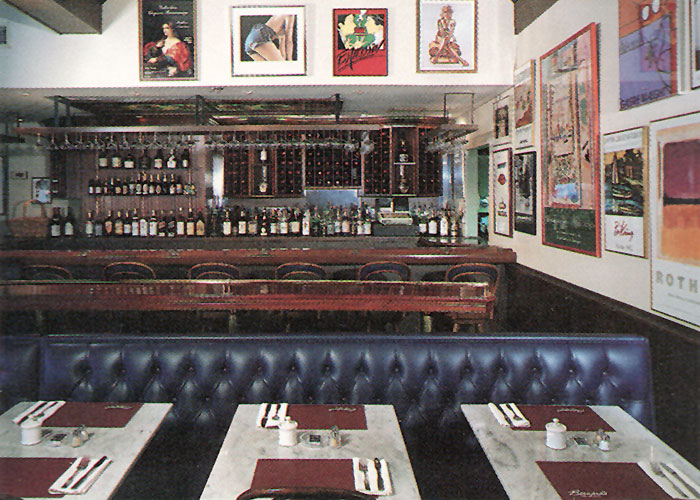

Bernard's was an informal 50-seat French

bistro. Its understated decor was much the same as Chez Louis, with

cream-colored walls adorned with colorful framed posters from Paris

art galleries. The ceiling was beamed and windows were trimmed with

little cafe curtains. Seating was on plain bentwood chairs at

bistro-style marble-top tables, with a few dark blue banquettes.

|

|

Bernard's Interior |

Douteau wanted Bernard's menu to be simpler

than the more formal Chez Louis.

At Chez Louis we had a menu that takes a lot

of preparation. I always felt we should offer the simpler foods that

are most common in France. They may sound pedestrian to some, but

these are the dishes many French people still eat every day.

The one-page menu included onion soup, crepes,

quiches, croque monsieur, salade Nicoise, terrines and charcuterie. There

were at least two specials a day, which could include a hearty cassoulet of meat, lentils and flageolets, or a spicy veal stew

simmered in white wine.

Douteau introduced the southern French

specialty

pan bania on Bernard's menu.

Knowing the appeal of

salads for Americans and, of course, sandwiches, I thought it

would be fun to present a salad sandwich.

The inside of a hard round roll or bun was

scooped out and filled with Boston lettuce, olives, tomatoes,

potatoes, hard-cooked egg, capers and a vinaigrette dressing, with

an anchovy option.

|

|

Bernard's Bar |

In December of 1983, Meyers and Douteau opened

Bernardís Food Boutique at 10 North Meramec. According to Douteau,

the gourmet marked started out as a charcuterie.

The concept of a

charcuterie is still strange to St. Louis. The way people live

here is more leisurely than, say, New York or Chicago. They

don't feel the necessity to come to a specific shop to buy

specific types of prepared foods.

Bad habits are easier than good ones,

you know. It is easier to get all your food items at one place.

Americans are not like Europeans who go to each little store and

specify the exact items they want.

The boutique featured an assortment of salamis,

hams, smoked duck, smoked chicken, Canadian bacon and cheeses. The

pastry counter offered a selection of cookies, tarts, pastries and

other sweets. There were croissants, baguettes and assorted breads.

Olive oil, teas, flavored vinegars and mustards were also available.

Bernardís Food Boutique was short lived. It

closed early in 1985.

* *

* * *

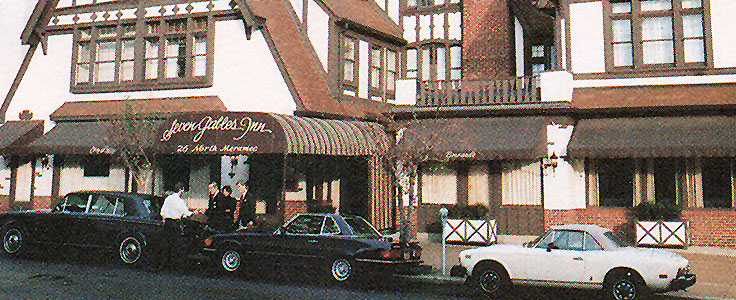

In April of 1985, Meyer purchased the Seven

Gables Apartment Building. Along with Douteau and Garrett Balke, a

St. Louis developer, he turned the 60-year-old Tudor-style building

into a 32 room hotel. They named their hotel the Seven Gables Inn.

When the Inn opened at the start of 1986, the

concrete-paved alleyway which ran between the two halves of the

H-shaped building had been removed. In its place, dark brown ceramic

tiles were laid and glass walls constructed on the ground level at

the front and rear to form an enclosed lobby. The lobby provided

access to Chez Louis and Bernard's on either side, and the

streetside entrances were closed. A 50-by-30-foot outside area in

the back of the lobby was landscaped and opened as the Garden Court

for outdoor dining.

Douteau explained the reason for incorporating

the two restaurants as part of the Inn.

It's a natural

extension to marry the restaurants with a small hotel. In

Europe, food is the main reason for the success or failure of a

hotel, while in this country it's often neglected with the rooms

becoming the focal point.

|

| Seven Gables Inn,

circa 1990 |

In August of 1987, Meyer acquired the Daniele

Hotel at 216 North Meramec in Clayton. The price was $4.6 million.

As part of a $1 million renovation program, the hotel's dining room

was renamed the London Grill.

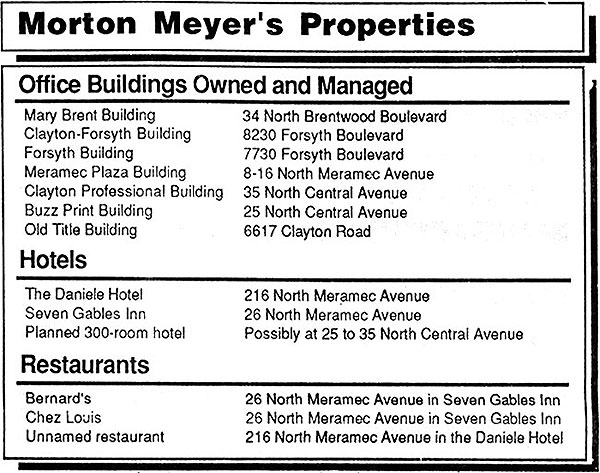

By September of 1987, in addition to his two

hotels and their associated restaurants, Meyer owned seven office

buildings in Clayton's central business district.

|

| St.

Louis Post-Dispatch, Sep 7, 1987 |

Meyer

also planed to open a 300-room "world-class" hotel in the heart

of Clayton.

I like doing new

things. We've got a parcel of land. We've also got serious

interest on the part of several chains to manage it. I can't

yet tell you where it will be.

Chez Louis and Bernard's continued to thrive

into the late 1980s. Bernard Douteau was particularly proud of his

namesake restaurant.

I like to think of it

as a classy, little neighborhood joint. It has a life of its own

apart from its neighbor, Chez Louis. While Chez Louis has

tablecloths, fine service and is a creative, fairly

sophisticated restaurant, Bernard's is a bistro serving a simple

tradition of casual food.

We have a good breakfast and lunch

trade ― especially lunch. And to do a good lunch business in

Clayton, you have to have a product that tastes good, is a good

value, is fresh and fast. In the evening, we have a good crowd,

as well, and we're also attracting the late night crowd after

they attend a movie or the theater.

|

|

1988 Chez Louis Menu

(click image to enlarge) |

1988 Bernard's Menu

(click image to enlarge) |

In September of 1988, Bernard Douteau left the

Seven Gables Inn and its restaurants to "pursue other interests,

including serving as consultant to Whitey's" ― Whitey Herzog's

restaurant at Union Station. Douteau was replaced as executive chef

by his assistant, David Zimmerman.

Zimmerman, a Clayton

native, received an associate's degree in the culinary sciences in

1986 from the Culinary Institute of American, after which he joined

the Seven Gables Inn as first sous chef. He was responsible for

developing menus for both Chez Louis and Bernard's.

|

|

|

David

Zimmerman, 1989

|

1989 Chez Louis Menu

(click image to enlarge) |

In 1988, Meyer announced he would build a 336

room hotel, the Clayton Hilton and Towers, on the southwest corner

of Maryland and Central. But the project faced opposition from

nearby property owners. The hotel was never built.

Morton Meyer died of cancer on July 21, 1990 at

the age of 59. By then, he was once again bankrupt.

Danny Meyer lamented his father's repeated

business failures.

He owned two hotels

in St. Louis, one of which ― the Seven Gables Inn, with its

French restaurant, Chez Louis ― met with critical acclaim. But

the other hotel ― the Daniele Hilton, with its mediocre London

Grill ― was a failure on every count.

My father had leveraged his entire

company to purchase these hotels, and also to purchase a medical

building in Clayton which he planned to reimagine and redevelop

into something big. However, by the time he had emptied the

building of its existing rent-paying tenants, the bottom had

fallen out of the economy. His funders dropped out, but not

before suing him.

Although Dad may have been an

inventive entrepreneur, he did not have the necessary emotional

skills or discipline, and he failed to surround himself with

enough competent, loyal, trustworthy colleagues whose skills and

strengths would have compensated for his own weaknesses. By

1990, shortly before he died of lung cancer at the age of

fifty-nine, he was once again bankrupt. Once again, he had to

inform his family ― his second wife, Vivian, and his three

children and their spouses ― about a failure. We all had a

painful sense of deja vu.

|

Morton Meyer

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Sep 7, 1987 |

In 1991, David Zimmerman left Chez Louis and

Bernard's to enter his family's flour business. Michael Holmes

replaced Zimmerman as executive chef.

In January of 1993, it was announced that Chez

Louis had been shuttered and would reopen as an extension of

Bernard's.

In February of 1995, Tim Weaver was named

executive chef of the Seven Gables Inn's dining spaces, including

Bernard's and the Garden Court.

In March of 1998, the owners of Harvest took

over management of the Seven Gables Inn's restaurants, operating

them all under the name Beaux Coo.

Copyright © 2023

LostTables.com

Lost TablesTM

is a trademark of LostTables.com. All rights reserved. |