|

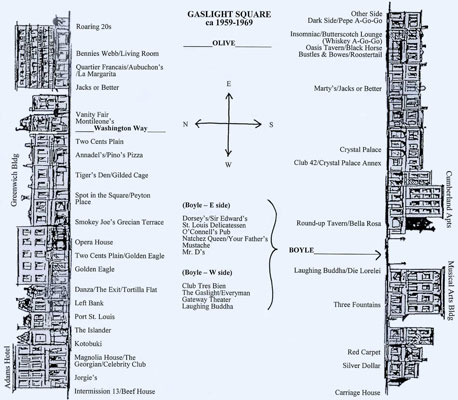

Gaslight Square On February 10, 1959, a tornado swept through St. Louis, toppling the KTVI tower and damaging the Arena on Oakland Avenue. It eventually bore down on Olive Street at its T-shaped intersection with Boyle.

The Musical Arts Building, on the southwest

corner of Boyle and Olive, was a landmark of the once fashionable

West End neighborhood. Opera star Helen Traubel studied voice there;

movie star Betty Grable learned to dance there; a young Vincent

Price had gone to the dentist in one of its offices.

* * * * The Musical Arts building was built around 1900. Private schools and fashionable shops were located in the area, frequented by residents of the big houses on Westminster Place. The neighborhood deteriorated to the point of becoming a notorious red-light district in the 1930s, but a revitalization began in the 1940s. Playwright William Inge lived there then, and the first version of his play "Picnic" (entitled "Front Porch") was produced at the Toy Theater at 455 Boyle.

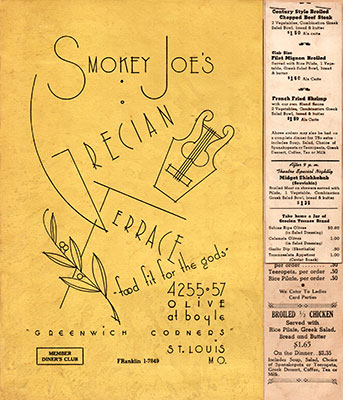

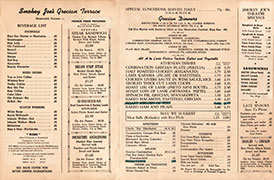

Alex Bayou opened

Smokey Joe’s Grecian Gardens in the early 1950s at 4255 Olive, with

its glowing pink neon sign and its much-photographed Greek columns.

By this time, the area became known as "Greenwich Corners."

In the mid 1950s, the area started to attract an assortment of saloons, eateries and antique stores, as well as the Adams Hotel, where baseball players like Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella stayed before they were welcome at the Chase. Richard Mutrux opened the Gaslight Bar in the Musical Arts Building, a favorite stopping place for businessmen heading home from work at day’s end.

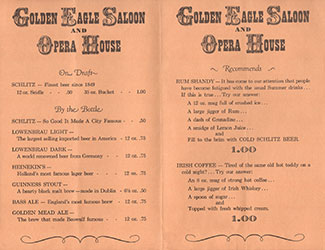

In November of 1956, Jimmy Massucci opened the

Golden Eagle, just west of Smokey Joe's. Then came Theo Goldston's Eagle’s Nest and Jay Landesman's

Crystal Palace, along with a drugstore, a

laundry and a few other places that nestled at the intersection of

Boyle and Olive. In those early days, from 1955 until the tornado of February 1959, the atmosphere was loose and casual. The various owners would meet for lunch in the drugstore, then sit on the curb, exchanging dreams and ideas. Everyone knew – and enjoyed – everyone else, and it was easy to wander from place to place, usually with drink in hand. The only threat was the streetcar that rumbled along Olive Street. * * * *

The 1959 tornado at first seemed to have

snuffed out the promise of a rebirth at Boyle and Olive. But then

something good began to happen. In the wake of the destruction came

sightseers and the insurance claim adjusters.

The infusion of insurance money led to quick recovery by the

building owners. Old places, like the Gaslight Bar, soon were operating

again, with more business than ever, and new places began to appear.

Soon, everyone was calling the area by a new name – Gaslight Square.

During the 1959-61 period, the openings were almost nightly. Jack Newman had Jacks or Better. The Dark Side of the Moon, generally know just as the Dark Side, brought cool jazz under the guidance of Spider Burks and the talents of Jeanne Trevor and the Quartet Tres Bien. Ed Dorsey brought a steak house, Mr. D’s, where Ceil Clayton played the piano. Bustles and Bowes brought ragtime, the Bella Rosa offered pizza, Marty Bronson made Marty’s a sing-along place, the Whiskey a Go-Go was an early disco. Singleton Palmer’s tuba boomed through the Opera House and to the street outside, and Sammy Gardner’s clarinet sang at Joe and Charlie’s. And there were more places. Wade DeWoskin opened Port St. Louis, Rosemary (Pat) O'Brien had Tortilla Flat, Myron and Becky Levy brought Japanese cuisine with Kotobuki. There was the Natchez Queen and the Butterscotch Lounge, the Blackhorse and the Roaring Twenties, the Left Bank, the Islander, the Club Tres Bien and the Living Room. The entertainment places and restaurants on the Square had increased tenfold. On April 17, 1961, the Smothers Brothers opened in a revue at the Crystal Palace. Second on the bill was an 18-year-old singer named Barbara Streisand.

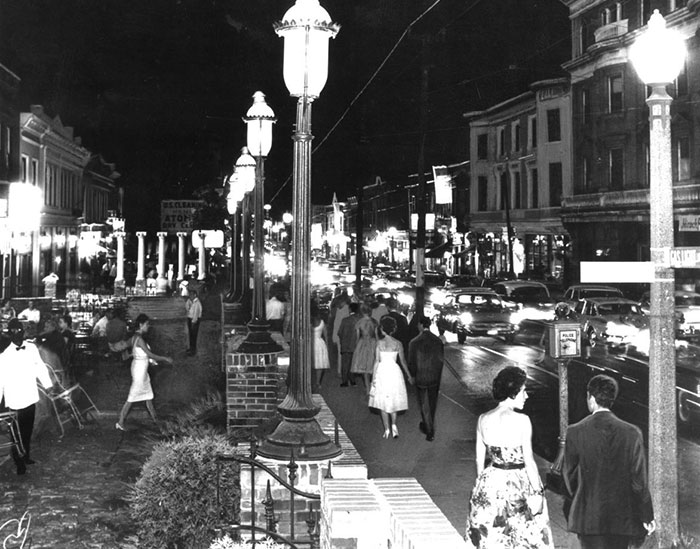

To many, this was the golden-age of Gaslight

Square. By the summer of 1961, Gaslight Square’s fame had spread far

and wide. Conventions were coming to St. Louis because of it.

Sightseeing buses were letting people off at Boyle and Olive on a

regular schedule. Parking had become a serious problem.

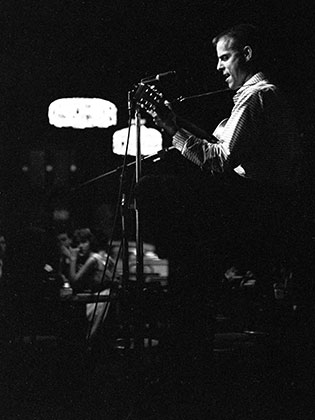

[Click links for articles on 2¢ Plain and Port St. Louis.] The Laughing Buddha One of Gaslight Square's pioneering establishments was Lee Young's Laughing Buddha. Opened on April 24, 1960, the coffeehouse, which did not serve alcohol, became a favorite night spot for underage folk music enthusiasts.

Young, an attorney from

Union, Missouri, originally opened his coffeehouse in the Boyle side

of the Musical Arts Building, between the Gaslight Bar and the

Westminster Emporium drugstore. One of the many handwritten signs

outside the Emporium pointed to the Boyle location. However, in

1961, when the drugstore space became available, Young moved The

Laughing Buddha to the corner of Boyle and Olive. The handwritten

signs were replaced by a smiling Buddha, designed by artist Ernest

Trova (enlarge images below).

The initial space, a former

barbershop, had the feel of a cozy living room. Well dressed

teens sat on sofas and chairs, with non-spirited drinks on

coffee tables, as they listened to their favorite folksingers.

The larger corner space had a more formal stage near the front, with tables and chairs. Coffees and pastries were served in the back of the room. Decades later, Lee Young reminisced about The Laughing Buddha from his law office in Union, Missouri.

The Laughing Buddha was a much quieter place than most of the Gaslight Square venues, except for its noisy espresso machine, which generally waited to roar into brewing mode until performers were in the midst of their most mellow songs. The cigarette machine had a weird voice that said "The Laughing Buddha thanks you" whenever a pack of cigarettes was purchased.

On the night of January 10, 1962, the Musical Arts Building was badly damaged by a spectacular fire. The following day, The Laughing Buddha was a mass of ice-coated debris.

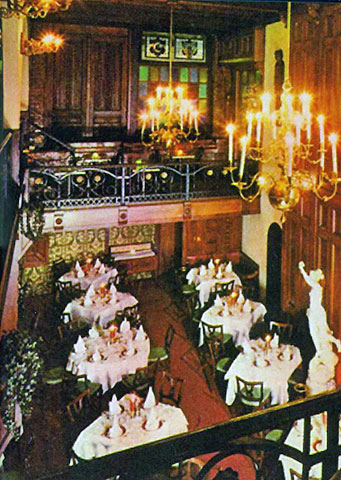

The Three Fountains

One of Gaslight Square’s most glorious moments

came on December 20, 1960 when Richard and Paul Mutrux opened The

Three Fountains restaurant in the Musical Arts

Building. It was one of the most elegant restaurants in the nation,

and it served French cuisine to match.

Richard and Paul Mutrux were two of 12 brothers and sisters, nine boys and three girls, including Paul's twin brother, George. Their father and their mother were both of French descent.

"We lived in a rambling house out in Ladue when

that was out in the country," Paul recalled, "and every time another

child or two was born my father added another room."

During World War II, Paul and his twin

brother George worked together as architects in Bordeaux, helping to

build an ordnance depot. They had an apartment and two French

cookbooks, one an Escoffier, and decided to master French cookery. Richard Mutrux saw things a bit differently.

The Three Fountains exuded luxury, with a

multilevel interior lavishly decorated with antique fixtures. The

wrought iron balcony railings were salvaged from the Grand Avenue

bridge. There were

burled mahogany panels from the Merchant’s Exchange

building. Two of the three fountains that gave the restaurant its

name were copies of the third, which came from a private garden in Vandeventer Place.

The Three Fountains

built their business around such

specialties as tripes à la mode de Caen (prepared by Paul), les

escalopes de veau Cordon Bleu (sometimes prepared by Richard),

cuisses de grenouilles à la Provençale and Paul’s own French bread.

There were also recipes from La Tassée du Chapitre, a Parisian

restaurant owned by Paul’s twin brother, George.

In 1964, Gaslight Square boasted 36 night spots, an estimated six-million-dollar business and a good national image. By the summer of 1968, it was down to six night spots, and The Three Fountains was being stripped of its antiques by Richard Mutrux.

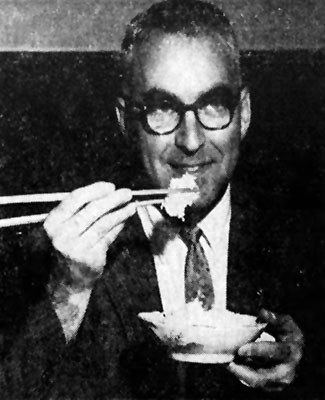

Richard Mutrux lived on until 2006. The Three Fountains died in the summer of 1968. It never reopened. Kotobuki In 1958, Ted Okamura opened the Tokyo Inn at 18th and Chestnut in downtown St. Louis. Myron Levy was a frequent customer at Okamura's restaurant. He was often one of the only customers, and customer and chef would sit and talk. "We will open another restaurant, Okamura and Levy," said Levy, "and put it where people can find it, in Gaslight Square."

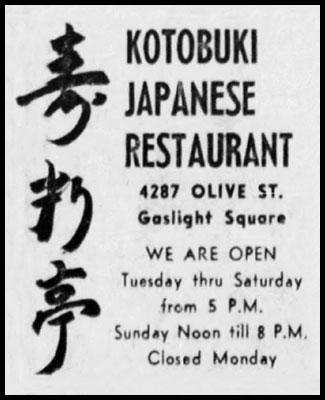

Levy was employed by the County Highway

Department; he knew nothing about the restaurant business. But in

October of 1960, Levy, his wife Rebecca and Okamura opened the

Kotobuki Japanese Restaurant at 4287 Olive in Gaslight Square.

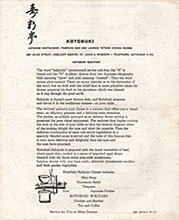

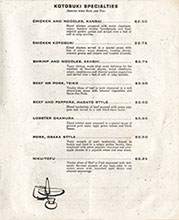

Okamura was stationed in the kitchen and Levy created all of the specialty cocktails. Becky Levy ran the front of the house, greeting customers and asking them to take off their shoes before they went upstairs onto grass mats. On weekends, there would be an hour or two wait for a table in the upstairs Tatami dining room, where the "Kotobuki Sukiyaki Dinner" was prepared tableside. The kimono clad servers were the Japanese wives of soldiers stationed at Scott Air Force Base.

Dinner included miso soup, sunomono salad, tempura, Japanese pickles, cookies, sherbet, tea and coffee.

The first floor dining room offered

conventional steaks and chops, in addition to a wide ranging

Japanese menu.

The Levys closed Kotobuki in 1965, as the charm of

Gaslight Square evaporated into noise and rowdy crowds. There were

plans to move the restaurant to the Central West End, but a space

large enough with sufficient parking never materialized.

O’Connell’s Pub

In the fall of 1961, Jack Seltzer, Ray

Gottfried and Frank Mormino opened O'Connell's Irish Pub at 454

North Boyle. After a few months, Mormino, who had opened Europa 390

in the Central West End, sold his interest to Dick Draper.

Norah McDermott was a customer in those early days. She would end up working as a server at O'Connell's for 36 years.

Richard Mutrux, from his vantage point at The Three Fountains, remembered the change of ownership.

Jack Parker grew up in a little house on the corner of Dover Place and Colorado Avenue in south St. Louis. "I was born in 1937, so it was the tail end of the Depression," he said, "and by the time I was cognizant, it was the second World War." He went to Cleveland High School, where he pledged Delta Psi Kappa – a frat more famous for good times than good grades. "I was kind of a goof-off, and I didn’t apply myself," Parker remembered. After he worked grooming racehorses and selling DeSotos, Parker moved into a cheap apartment on Olive Street and got his first good bartending job at The Opera House on Friday and Saturday nights, when Singleton Palmer was there. Slowly, Parker educated himself, determined "to be able to discuss Albert Camus with the guy next to me on the bar stool." Parker eventually became the bartender at O'Connell's, supervising both drinks and the tiny grill that prepared hamburgers and London broil, the only menu items. A few months later, he added a soup tureen.

In 1965, when profits started to fall and the

pub’s owners decided they wanted out, Parker arranged to take over

the business.

Parker hired Norah McDermott as a server in 1966.

The burger was the mainstay on O'Connell's menu, introduced by a guy who’d tended bar at P.J. Clarke’s in New York. All the other burgers in St. Louis – even Medart’s – were flat-grilled. The O’Connell’s burger was thick, made with top grade beef, and it could be ordered rare.

There was also roast beef, cooked to order with

or without au jus, the Coney Island, with a premium frankfurter

grilled to perfection, and a salad with "Mayfair" dressing. Daily

specials including fish and chips on Friday, and there was a soup of

the day and chili.

By 1972, the once happening Gaslight Square was nearly vacant and Parker had to make a decision.

He packed up everything and moved to a 1905 Anheuser-Busch tavern on an isolated, industrial stretch of South Kingshighway. He's still there today. * * * *

Theories abound as to what caused the demise of

Gaslight Square. Some believe its very success is what killed it.

Its growth lacked any kind of control. By 1965, the area was

becoming dominated by discotheques with go-go dancers and loud

recorded music. The charm of the original Square evaporated into

noise and rowdy crowds.

One after another, the restaurants and bars

closed or moved.

Copyright © 2022

LostTables.com |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||