|

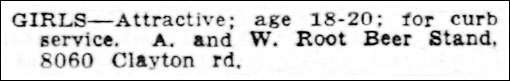

Fitz's Drive-In In 1919, Roy Allen set up a root beer stand at a parade in Lodi, California honoring veterans returning from WWI. He purchased the formula for his root beer from a pharmacist in Arizona. With the success of his first stand, Allen soon opened a second in nearby Sacramento. It was the first "drive-in" featuring "tray-boys" for curb side service. In 1922, Allen took on a partner, Frank Wright. The two partners combined their initials and formally named their beverage A&W Root Beer.

In 1924, Allen bought out Wright and pursued a

franchising program. To ensure the quality of the root beer, he sold

A&W concentrate exclusively to these franchises, the unique blend of

herbs, spices, barks and berries remaining a proprietary secret. By

1941, there were 260 A&W franchised outlets operating in the United

States.

By 1925, there was an A&W Root Beer stand in

St. Louis at 205 North 6th Street. And by 1942, there was a stand at

8060 Clayton Road, on the south side of the street, just east of

Brentwood Boulevard.

The owner of the Clayton Road stand is unknown. What is know is that by May of 1947 it was no longer an A&W stand. The original owner may have let his A&W franchise lapse or another party may have purchased the stand, but not the franchise.

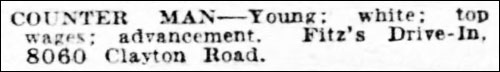

In any event, by May of 1947, James L.

Fitzpatrick owned the root beer stand at 8060 Clayton Road, and he

and his wife registered its new name with the state of Missouri on

October 19, 1948. The A&W Root Beer Stand became Fitz's Drive-In.

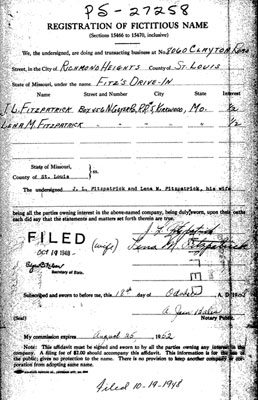

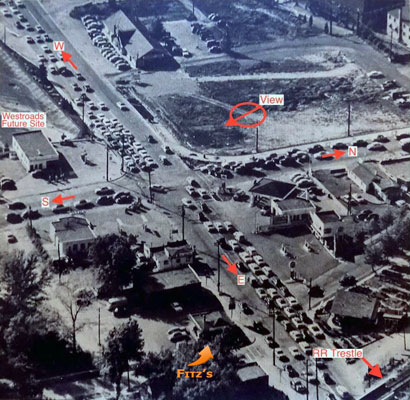

Fitz's Drive-In was just east of the Shell station on the south side of Clayton Road, and just west of the railroad trestle. It was a squarish little ramshackle structure, which retained the orange and white A&W colors. It also retained A&W's large FLASH YOUR LIGHTS FOR SERVICE; PLEASE DO NOT SOUND HORN sign on the side of the building. Once James L. Fitzpatrick transformed the stand from A&W to Fitz's, he had to find another source for his root beer; he didn't have access to the A&W concentrate sold exclusively to A&W franchises.

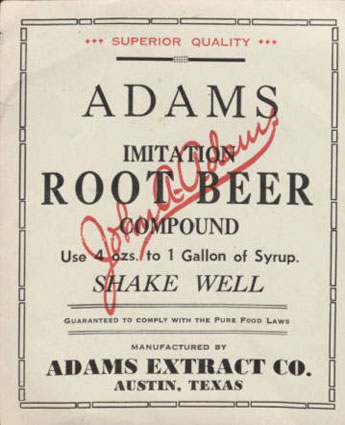

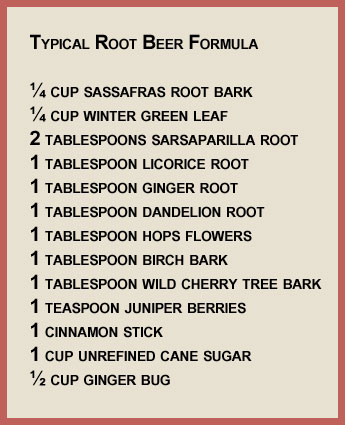

Fitzpatrick could have obtained a replacement

concentrate from any of a number of commercial sources throughout

the country, such as the Adams Extract Company in Austin, Texas or

the Northwestern Extract Company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. More

likely, he ordered individual ingredients and mixed his own brew. He came

up with a "secret formula" which delighted customers for thirty

years.

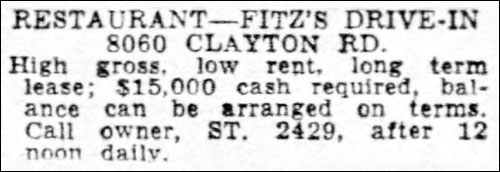

In May of 1952, Fitzpatrick placed an ad in the

Business Opportunities section of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. The

drive-in which bore his name was for sale.

Fitz's Drive-In was acquired by Arthur J. Goldmann. Goldmann was 48 years old at the time. One account states he had been an employee of Fitzpatrick's at the root beer stand. On the 1940 census, 12 years earlier, he listed his occupation as a fireman. Goldmann's most significant addition to Fitz's was his creation of the Kitchenburger, with its secret sauce. "He was trying to make a special concoction for a special customer one day, is the way he explained it to me," remembered Philip O'Brien, Goldmann's grandson. "He was playing with a relish base, and he added onions and some other things, and there it was." The sauce added a real charge to the burger, which itself was better than ordinary. It had overtones of Thousand Island dressing, but with other ingredients. Fitz's Kitchenburger, with its secret sauce, became the stuff of legends.

After Fitz's closed in 1976, the family

continued to keep the

sauce's recipe a secret. However, in 1985, Dorothy O’Hare of St.

Charles sent the recipe to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. The recipe

was dated December 19, 1967.

After operating Fitz's Drive-In for 20 years,

Goldmann retired in 1972. He and his wife moved to St. Petersburg,

Florida.

Goldmann son-in-law, Philip J. O'Brien, took over operation of Fitz's. In 1966, O'Brien had opened O'Brien's Restaurant and Lounge at 1030 Brentwood. After Fitz's closed, O'Brien's continued to use many of the drive-in's recipes. O'Brien's 28-year-old son, Philip A. O'Brien, was running Fitz's in 1976 when the St. Louis County Health Department refused to renew its license. "They told me that our plywood construction and sloping floors didn't meet their standards," O'Brien explained. "I was perfectly willing to tear the building down and build a new one," O'Brien continued, "but the property owner wouldn't give a long-term lease. I offered to build it myself, by the way. I didn't ask him to build it for me." While business had gone through its ups and downs, O'Brien estimated that Fitz's was still serving between 200 and 250 hamburgers a day, plus about 10 dozen hot dogs. "I've been here all my life," he said, "and my father and my grandfather before me, and now it's over. But I still have the recipe for the kitchen sauce and the formula for the root beer, and I guess I'll have to find someplace else."

As for the root beer, Fitz's had not been

making its own for two years, since the compressor on the ancient

machine they used broke down and O'Brien discovered that parts were

no longer available to repair it.

O'Brien mixed the last batch of secret sauce on

August 30, 1976 and Fitz's Drive-In closed its doors on August 31.

In 1986, architect Tom Cohen, who had hung out at Fitz's in his high school days, contracted with the company that supplied the flavor extracts for the original Fitz's root beer to do the same for him. Cohen bought a carbonator and played mad scientist in his kitchen, perfecting the blend of flavors. Then he tracked down a bottle manufacturer and found somebody to bottle his root beer. Michael Alter and Alan Richman, both of whom had experience in the food business, liked Cohen's version of Fitz's root beer. They got together with Cohen and hatched the idea of a root beer micro-brewery combined with a restaurant, which they opened at 6605 Delmar in University City in 1993. Fitz's lives on.

Copyright © 2019 LostTables.com |