|

Tony Faust's Anthony Edward Faust immigrated to New York City from Germany in 1853 at the age of seventeen. He moved to St. Louis after a brief stay in Dubuque, Iowa, where he settled in Frenchtown, an immigrant sanctuary south of the city along the Mississippi River. Faust worked for some time as an ornamental plasterer. But in 1861, a month after the start of the Civil War, he was shot in the left leg when a soldierís gun accidentally discharged as Faust watched the volunteer militia march through the streets. No longer physically capable of working in the plastering trade, Faust decided to take up barkeeping, and opened a small cafť at 295 Carondelet in his Frenchtown neighborhood. Faust's little bar thrived. In 1870, he moved it 20 blocks north to Broadway and Elm, next door to the Southern Hotel and across Broadway from the Olympic Theater, both leading institutions at the time. Faust renamed his restaurant Tony Faust's Oyster House & Saloon. People loved Tony Faust. He was a short man with a ruddy complexion, bushy mustache and an ever-present bowler hat. He moved about his restaurant, visiting and joking with customers. He always had a good story to tell.

While Tony Faustís restaurant was a landmark in its

own right, its early success built on its oysters, its business wasnít hurt by its location adjacent to

the Southern Hotel. Built in 1863 and proclaimed by the New York

Times to be "unsurpassed in any building of the kind in the land,"

the hotel was state-of-the-art and the largest in St. Louis. Tony

Faust's Oyster House & Saloon stood on the southwest corner of the

block and Faust leased the property from the hotelís owner.

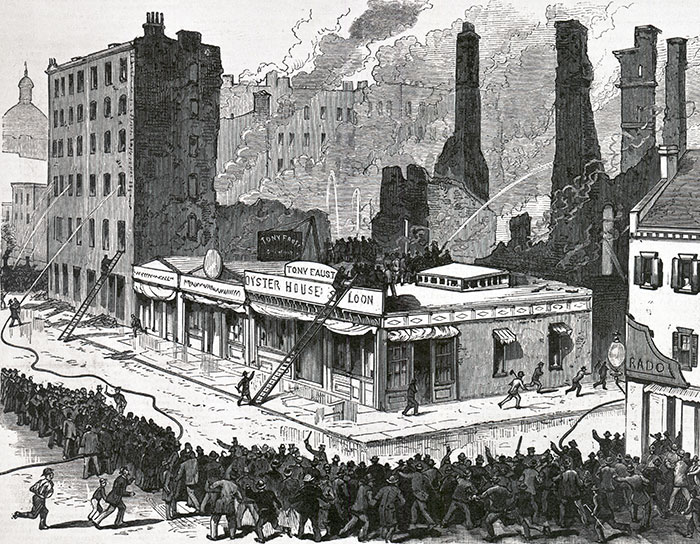

Plans to rebuild the Southern began immediately. Not to be outdone, Tony Faust set to work himself, the rebuilding of his restaurant culminating in a grand opening on July 4, 1877.

In 1879, Faust created a "garden terrace" on the roof of his restaurant building. Opened every spring, when the weather turned warm, the terrace provided a garden-like setting with the comforts of a restaurant.

In addition to serving oysters in his

restaurant, Faust began

selling oysters retail and wholesale as early as 1876. This side

business was a valuable addition and it

prospered. On April 1, 1880, Faust opened his Fulton Market under

the Southern Hotel, adjoining his new building. The Fulton Market

offered an impressive variety of fish, as well as vegetables,

cheeses, wild game, canned goods and condiments. Faust guaranteed

freshness and top-quality products to his customers.

Tony Faust's restaurant had the advantage of being located in the theater district, across from the Olympic Theater. Visiting troupes stayed at the Southern Hotel and dined at Faustís restaurant. Actresses dined in the ladies' restaurant upstairs, among them such players as Julia Marlowe, Julia Arthur, Mary Anderson, Della Fox and Maude Adams. Among noted men of the stage who crossed the street for refreshments at Faust's after their turn at the Olympic were Edwin Booth, Lawrence Barrett, Joseph Jefferson, Roland Reed, James O'Neill and Maurice Barrymore. Faust hosted grand after-show dinners and toasted the actors and actresses on their performances. Joseph Jefferson originated a dish which later became a Faust specialty. One night after a performance at the theater, he went to the restaurant for a midnight supper and, after poring over the menu without satisfaction, glanced up and said, "Quail on sauerkraut." The unexpected order was filled without question and the dish thereafter was a favorite.

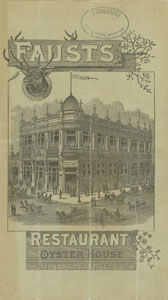

Ten years after the Southern hotel fire, Faust

tore down his restaurant and built anew. He had traveled around

Europe studying architecture, kitchens, equipment and foods. When

Faust held the grand opening for his new establishment in 1889, few could believe

the size and luxury. Even the 72 foot by 107 foot basement, with high

ceilings, wine cellar, laundry and cooking rooms, was

state-of-the-art. The "magnificent, spacious bar" and gentlemenís

restaurant were located on the ground floor, with the kitchen in the

rear. The ladiesí parlor was located on the second floor, with its

own entrance, decorated with oil paintings and mosaic flooring.

Estimated to cost $98,000, the restaurant could accommodate 1,500

people.

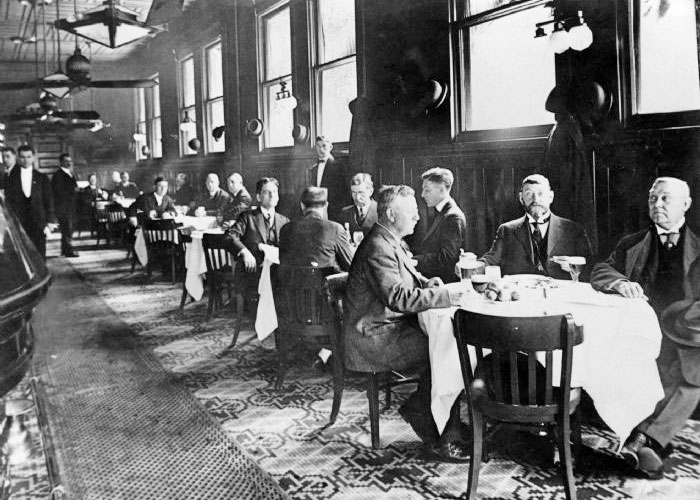

Dedicated to his business, Faust lived next door to his restaurant. He took customer service seriously and worked in tandem with his staff. He employed as many as 100 people at a given time, the majority German. Faust was known to be liberal with money, and his employees were likely paid well. Until 1895, every employee was allowed as much beer as he desired throughout the workday.

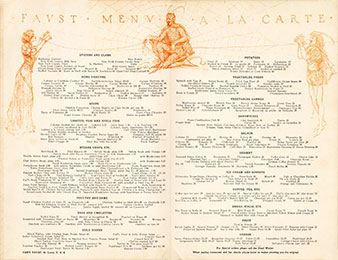

Tony Faustís restaurant was commonly referred to as

the

"Delmonicoís of

the West." The Delmonico brothers adopted the Parisian style menu

for their New York restaurant, which offered choices of foods with

individual prices rather than set meals with set prices. Faust's

menu offered the most extravagant Gilded Age

dishes and a glittering array of liquors, wines and champagnes. By the turn of the century, Faust's had become the center of St. Louisí social life Ė the place where the rich, powerful and famous could always be found. Adolphus Busch lunched there almost daily, along with other beer barons and leading businessmen, at the "Millionaires Table." Busch and Faust were close friends and became in-laws when Faustís son Edward married Buschís daughter Anna Louise. They and a handful of other German-Americans were among the most powerful men in the city, influencing politics, economics, and culture. For a time, Anheuser-Busch brewed a specially branded "Faustís" beer that was sold in the establishment and at retail.

Faust was known

for his New Year's Eve parties. Seats in his restaurant were often

reserved a year in advance. In 1887, guests each received a card

with a caricature of Faust getting out of bed on New Year's Day,

with cherubs blowing trumpets and with salutatory messages in both

French and German. The most sought-after seats were located at the

Faust-Busch table.

In the summer of 1906, while touring in

Germany, Faust was involved in an accident. He was in a carriage when

the horses were spooked and bolted. At age 70, Faust's injuries were

serious. In the late afternoon of September 28, 1906, Faust's son

Anthony received a cable that his father had died.

After his death, Tony Faust's restaurant was

run by his son Anthony, until he fell ill in 1911. The St. Louis Catering Company

took over operation until 1915, when Henry Dietz, Tony Faust's former chef, purchased the restaurant.

The Southern Hotel saw its last guest in 1912 and the Olympic Theater's last season was 1916. Once part of a thriving city center, Tony Faust's iconic restaurant languished as the city's commercial and entertainment districts moved westward. While many prosperous St. Louisans still ate their lunch at Faust's, the night business fell off to so great an extent that Henry Dietz was forced to close the restaurant.

Tony Faust's restaurant closed its doors for

the final time on June 30, 1916. German songs were sung by the

waiters, some of whom had been employed at Faust's for more than thirty

years.

In 1933, the Faust building was razed, along with the adjacent Southern Hotel building. When the Adamís Mark Hotel opened in the same general area in 1986, it gave a nod to history by naming its signature restaurant Faustís. And the Faust name lives on in St. Louis County. Faustís grandson, Leicester Busch Faust, and his wife donated their extensive estate to the county in the late 20th century to create Faust Park. Works cited: Terry, Elizabeth. Oysters to Angus: Three Generations of the St. Louis Faust Family. St. Louis: Bluebird Publishing, 2014.

Copyright © 2023 LostTables.com |