|

Chinatown

In the last decades of the nineteenth century,

St. Louis was a city of rich ethnic diversity. Immigrants from other

continents composed one third of the city’s population. St. Louis

was the fourth largest city in the United States at the time.

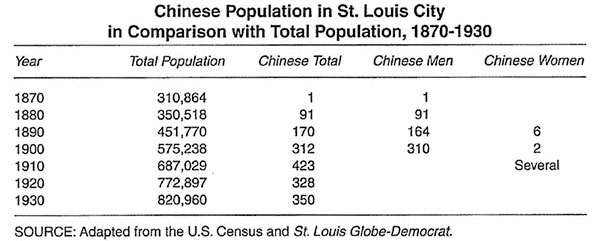

It is during this period that Chinese started

arriving in St. Louis. The first recorded Chinese immigrant was Alla

Lee, who arrived in 1857 and opened a small shop on North Tenth

Street selling tea and coffee. By the end of the nineteenth century,

the Chinese community in St. Louis had grown to about three hundred.

The earliest Chinese settlers in St. Louis

congregated in an area between Seventh, Eighth, Market and Walnut

Streets, which became the Chinatown of St. Louis, more commonly

known as Hop Alley. The name was widely used to represent the

district where Chinese hand laundries, merchandise stores, grocery

stores, herb shops and restaurants were located.

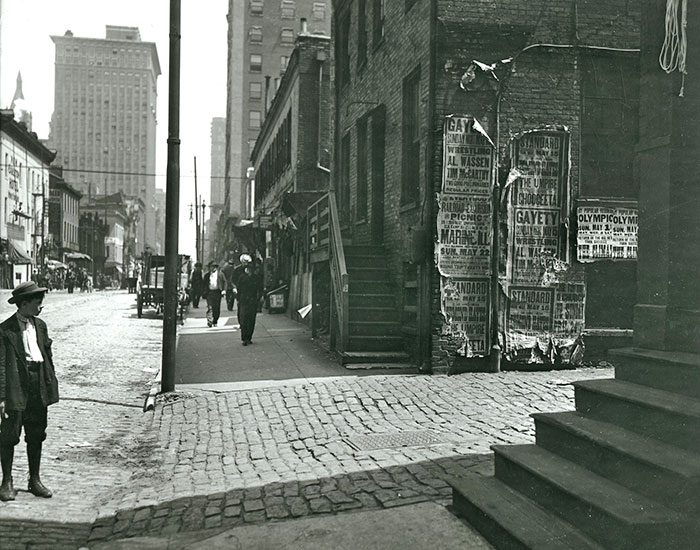

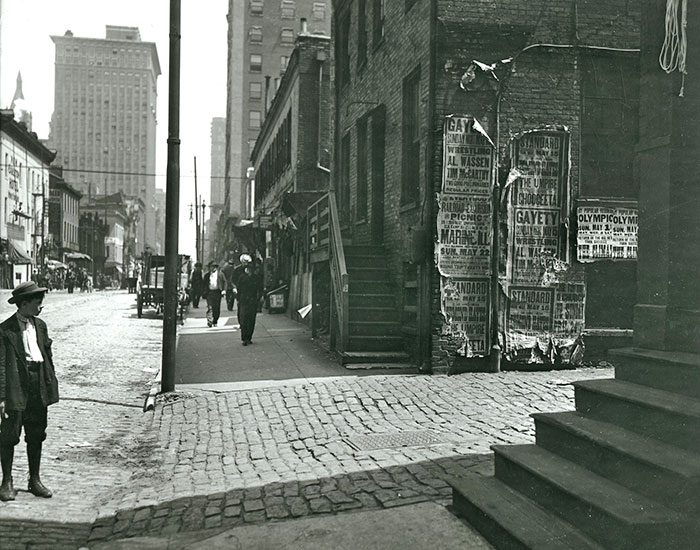

|

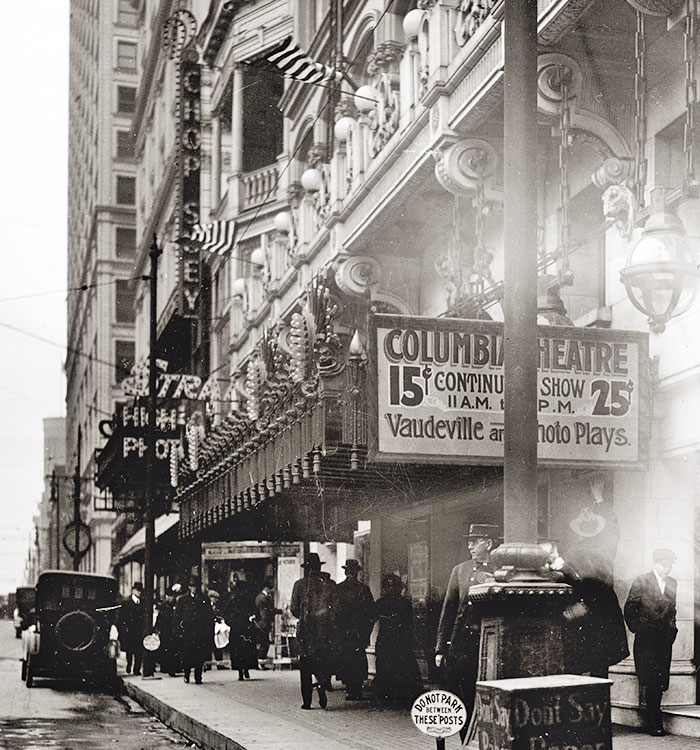

| Hop

Alley looking north on Eighth Street between Walnut and

Market Streets, 1910 |

Chinese restaurants were initially started to

satisfy the needs of Chinese bachelors. They served

authentic Chinese dishes that appealed mainly to

Chinese.

In January of 1894, Theodore Dreiser, then a 23

year-old reporter for the St. Louis Republic, visited the Kee

Hong Kee restaurant at 19 South Eighth Street while researching a

story about the Chinese in St. Louis.

The first dish set on

the bare table was no longer than a silver dollar and contained

a tiny dab of mustard in a spoonful of oil. Three dishes of like

size followed, one containing pepper jam, the others meat

sauces. Tea was served in bowls, and was delicious. The duck,

likewise the chicken, was halved, then sliced crosswise after

the manner of bologna sausage, and served on round decorated

plates. One bowl of chicken soup comprised the same order for

two, which was served with dainty little spoons of chinaware,

decorated in unmistakable heathen design. Rice, steaming hot,

was brought in bowls, half platter. Around the platter-like edge

were carefully placed bits of something which looked like wet

piecrust and tasted like smoked fish. The way they stuck out

around the edges suggested decoration of lettuce, parsley and

watercress. The arrangement of the whole affair inspired visions

of hot salad. Celery, giblets, onions, seaweed that looked like

dulse, and some peculiar and totally foreign grains resembling

barley, went to make up this steaming-hot mass.

St. Louis Republic, Jan 14, 1894

As Chinese restaurateurs expanded

their menus, chop suey shops opened in Hop Alley. Chop suey could be

easily prepared and was widely accepted by non-Chinese patrons as

representative of Chinese food.

The origin of chop suey is widely debated. St

Louisan Emily Hahn presented one popular theory in her book on

Chinese cooking.

Two dishes that

Westerners do know and repeatedly order are chop suey and chow

mein. This is a great pity, for while chow mein can be good

enough, there is little one can say in favor of chop suey, a

dish unknown in China. One explanation of its origin is that the

dish was born when the famous 19th Century diplomat Li Hung

Chang, traveling in the West as the Chinese emperor's emissary,

got indigestion from rich foreign food at banquets he had to

attend. He had so agonizing an attack of biliousness following a

hard week's banqueting in the United States that his aide Lo

Feng-luh suggested a bland diet. Between them the gentlemen

thought up the plainest possible dish – a concoction of celery

and other vegetables sautéed with a little pork. Thus was chop

suey born. The

other standby of Chinese restaurants in the United States, chow

mein, is something else again. It had an honorable origin in

China, where it is often eaten as a snack or light meal. When

well prepared, it can be very good. (I still remember the

chicken chow mein I ate on my first date, hundreds of years ago

in St. Louis, in a Chinese restaurant where we were awed and

delighted by lovely hanging lamps with red silk panels that gave

out little illumination, and a romantic table of black wood

inlaid with bits of abalone shell or possibly genuine

mother-of-pearl. All the mysterious East was ours in Missouri,

and chow mein too.)

The Cooking of China, Time-Life

Books, 1968

Orient Restaurant

Jo Lin was born in San Francisco in 1883. He

arrived in St. Louis in 1906 with no family and little money. By

1916, he owned the Orient Chop Suey Restaurant at 419 North 6th

Street, over the Strand Theater.

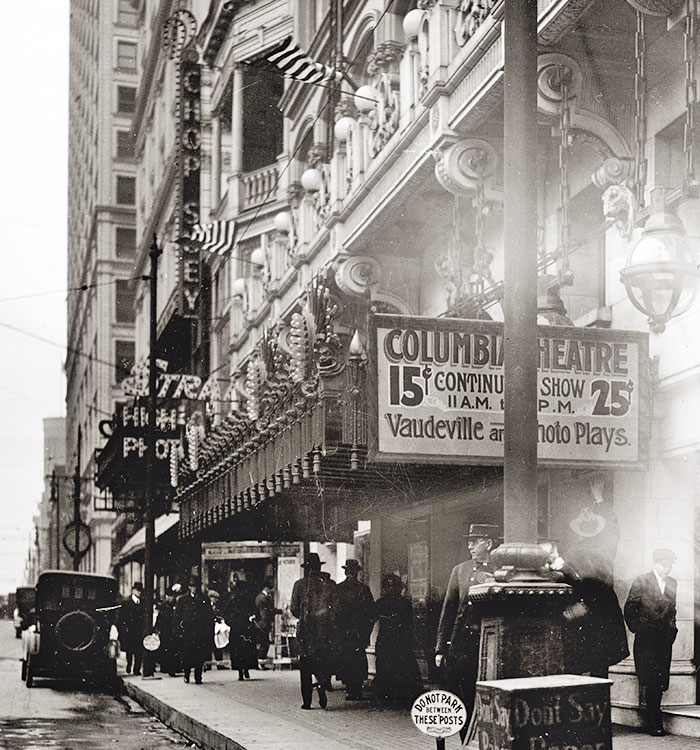

|

| Orient

Chop Suey Restaurant, 419 North 6th Street, 1916 |

Advertising Men – You

Are Invited to Visit The Orient Chop Suey

More than 400 Chinese and American

dishes prepared by the most famous Chinese chefs in the country.

Enjoy these good things to eat amid the luxurious surroundings

and quaint Chinese decorations. We especially cater to ladies’

afternoon tea parties in our richly designed tea room. In our

specially arranged banquet room we are prepared to take care of

small banquets.

The St. Louis Star, Jun 7, 1917

Joe Lin was forced to move his restaurant when

he lost the lease on the space above the Strand Theater. On March

19, 1926, he reopened the Orient at 414 North 7th Street.

The opening today of

the new $40,000 Orient chop suey restaurant, 414 North Seventh

street, is the realization of success for Joe Lin.

Lin arrived in St. Louis in 1906 with

65 cents in his pocket and only one acquaintance. Today he is

opening one of the largest chop suey restaurants in the central

west. Joe admits he is wealthy, but he says he does not know

just how much he is worth. He says:

"To succeed in any business, but

especially the restaurant business, you must cater to all the

people, regardless of who they are."

The St. Louis Star, Mar 19, 1926

|

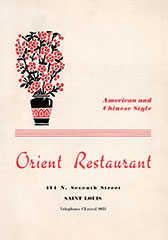

| Orient

Restaurant, 414 North 7th Street, 1935 |

On February 4, 1929, Eugene O'Neill's

Strange Interlude opened at the American Theater. The nine act

play ran from 5:30 p.m. until 11:00 p.m., with a dinner intermission

at 7:40, following the fifth act. Theatergoers could walk three

blocks north on Seventh Street to the Orient for a bite to eat and

then return to the American at 9:00 for the play's final four acts.

|

|

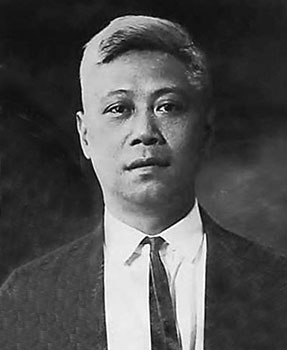

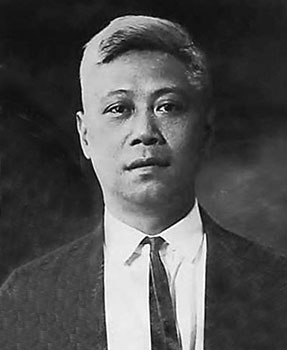

| Joe

Lin, 1924 |

St.

Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb 5, 1929 |

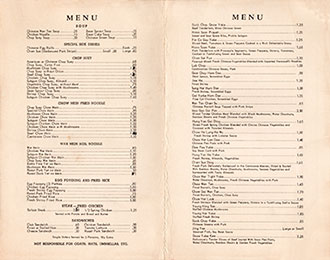

The Orient offered an

exotic dining experience, complete with hanging red lanterns and

steaming pots of Darjeeling tea. The chicken

and

pork chow mein were customer favorites. The chow mein wasn't

prepared ahead of time like most other restaurants. The vegetables

were cut up and kept crisp and cold, then cooked with the meat when

ordered.

|

|

|

1940s Orient Restaurant

Menu

(click image to enlarge) |

Joe Lin held the honorary title of Mayor of

Chinatown. He was the president of the On Leong Merchants Association, the dominant community organization

in St. Louis Chinatown, serving as an unofficial local government

for Chinese immigrants. Always neatly dressed and dignified, he was

a familiar figure in St. Louis courts, where he frequently served as

an interpreter in cases involving other Chinese.

Joe Lin died on December 14, 1947 of a brain

tumor. He was 64 years old. His funeral procession included a

30-piece band and 46 limousines. Chinese leaders from 28 cities

attended the service.

|

| Orient

Restaurant, 414 North 7th Street, late 1940s |

In early 1953, the Orient moved one block north

and across the street to 505 North Seventh in the St. Charles

building. The restaurant's ownership had passed on to Mark Raymond,

David Wai Foon Lee and Eng Mow.

The Orient continued serving chop suey and chow

mein until it closed in late December of 1967.

|

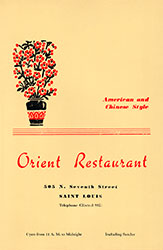

|

|

1950s Orient Restaurant

Menu

(click image to enlarge) |

Asia Cafe

Gee Leong was born in China in 1870 and

immigrated to the United States in 1890. By 1918, he was living in

St. Louis and had opened The New Republic Chinese restaurant at 825A

Locust.

Gee Leong became president of the On Leong

Merchants Association and assumed the title of Mayor of Chinatown.

In 1924, he married 19 year-old Chin Shee, who had immigrated to St.

Louis from China. Their three children were all born in Hop Alley –

Wing in 1924, Quong in 1928 and Annie in 1934.

On October 1, 1932, Gee Leong opened the Asia

Restaurant at 712-714-716 Market Street, in the same building which

housed the On Leong Merchants Association on the second floor. The

restaurant would come to be known at the Asia Cafe, with its address

morphing to 720 Market.

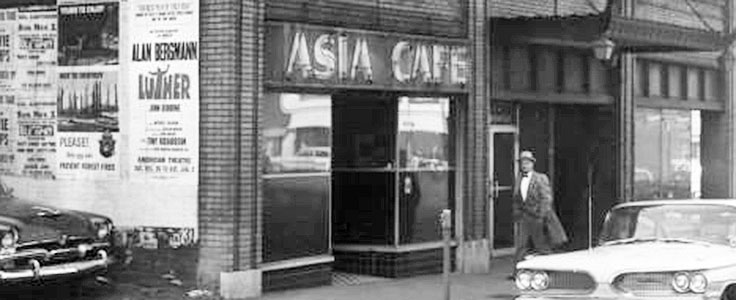

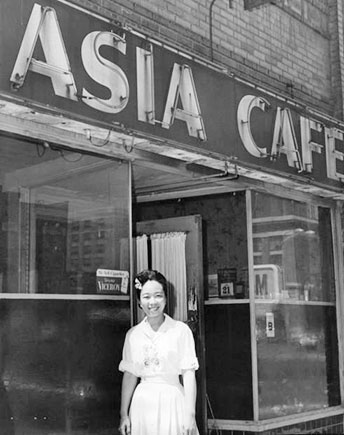

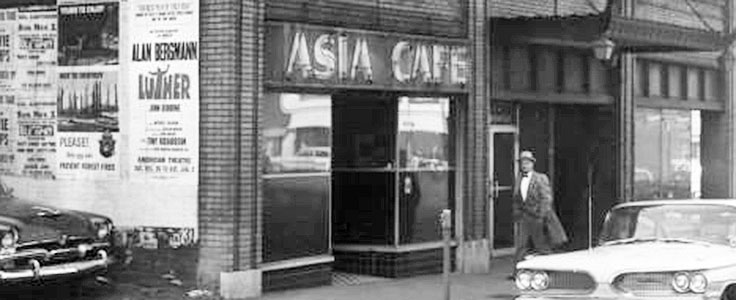

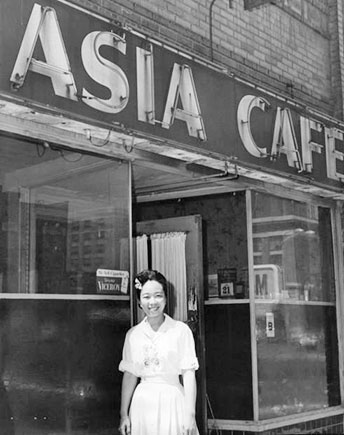

|

| Asia

Cafe, 720 Market Street |

For real Chinese

dishes, Asia restaurant, at 712 1/2 Market street. Up a long

flight of stairs and nothing to see when you get there, unless

there are Chinese in the back room using chopsticks. Food is

excellent and inexpensive. If you feel you really ought to try

bird's nest soup or shark fins, order a day or so ahead of time.

Authentic chow mein, chop suey, eggs fooyoung, with rice, tea,

fruit preserves in honey and almond cakes, can be had without

notice. Make friends with Nin Young, the proprietor, and he'll

take you back stage to show you how he sprouts his own beans,

and prepares the odd ingredients like water chestnuts and dried

mushrooms. No spirits available.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Jan 17,

1937

Nin Young immigrated to San Francisco from

China in 1917 and came to St. Louis in 1919. He had worked for

Gee Leong at The New Republic and followed him to the Asia.

Gee Leong died in July of 1937 at the age of

67. Nin Young purchased the Asia and became a step-father to Wing, Quong and Annie Leong.

Chin Shee continued to work at the restaurant and lived in the rear

of the building with her children.

Annie Leong recalled her life in the restaurant

in the 1930s and 1940s.

The whole family

worked. If you didn’t get paid, it was okay. My mother worked in

the dining room and kitchen of the restaurant. My dad worked as

a chef. During the depression era, they survived and they made a

living out of it. . . . We worked seven days a week, from eleven

o’clock in the morning to midnight . . . . We [she and her

brothers] did everything. We wrapped wontons, we took care of

the dining room area and we set up restaurant. Then if they

needed you, you could cook too. So we did whatever was needed.

It was just natural, and you just did it. We were going to

school besides that and we had to do our homework too. You were

studying between customers. After school, you would study, and

it would get busy during dinner hours, and you took care of all

the customers. In between, you would study a little, and then

you took care of customers. After the dinner rush was over,

maybe about eight o’clock or something, you could really have

more time to study. I guess that was something you never thought

about and that was something you did.

The Asia Cafe was a favorite meeting place for

the Chinese community. Patrons met to talk in their native

language, to read the two daily Chinese language newspapers and to

play mahjong.

Annie Leong became manager of the restaurant,

along with her step-father.

Many politicians and

show people – from the American Theatre and even the Grand – ate

with us, Sometimes when a judge came for lunch, the lawyers in

the room would stand up and say, "Your honor!"

We had "stir fries" back then, by the

way. It took most Americans many years to discover them.

* *

* * *

As buildings in the Chinatown neighborhood were

sold for parking lots, families moved out. While the older

generation of Chinese residents worked in restaurants and laundries,

the younger generation had educational opportunities and became

engineers, accountants and chemists.

In 1965 it was announced that the building

which housed the On Leong Merchants Association and Annie Leong's

Asia Cafe would be leveled to make way for a commercial development

associated with the new downtown sports stadium.

I was born in this

building. It's home and I don't want to leave. I think some of

the older Chinese people will be lost when they're forced to

move out of this block. I guess I feel like a landmark myself.

This neighborhood with its

closely-knit, old-fashioned Chinese families built character.

Juvenile delinquency didn't exist in Chinatown.

Nin Young planned to retire and Annie Leong was

hesitant to run the restaurant on her own.

These days it's very

hard to get an authentic Chinese cook. I can cook, but I'm slow.

If a good Chinese cook could be persuaded to come here, he'd

probably come from San Francisco or New York, and he wouldn't be

happy because we don't have the Chinese population here that

they do in those towns. He'd get lonely.

|

|

|

Annie Leong, Asia Cafe,

1965 |

The Asia Cafe closed on August 1, 1965. The

restaurant was the last business standing in Hop Alley. The land

between Seventh, Eighth, Market and Walnut Streets would be cleared

to make way for the General American Life building.

The last vestige of Chinatown had disappeared.

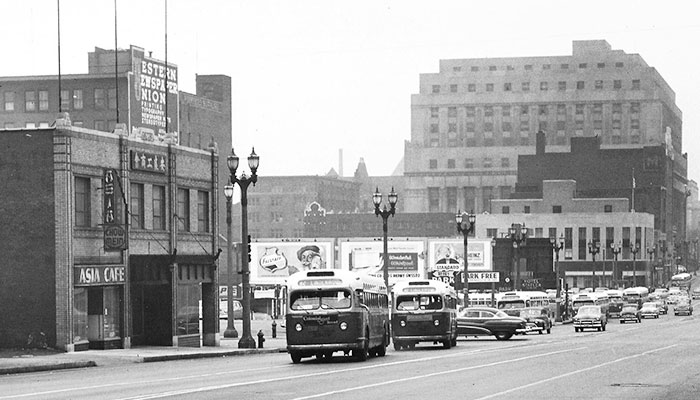

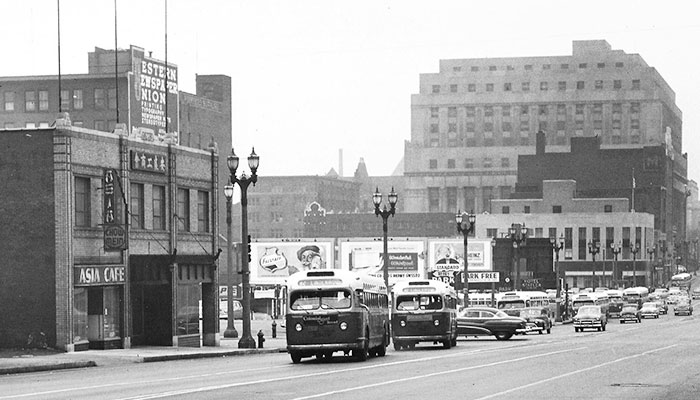

|

Looking

west on Market Street from Seventh Street, 1965

|

|

| Looking

west on Market Street from Seventh Street, 2019 |

Copyright © 2023 LostTables.com

Lost TablesTM

is a trademark of LostTables.com. All rights reserved. |