|

Big Boy's

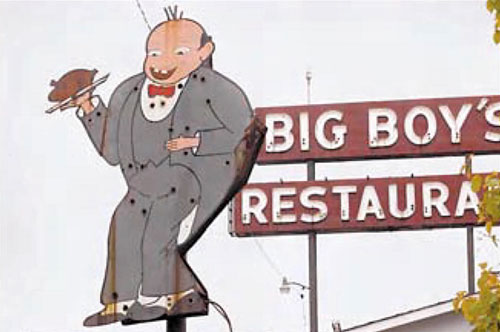

For years, motorists who drove along Route 40

between St. Louis and Kansas City saw roadside signs advertising

fried chicken at Big Boy's Restaurant in Wright City, Missouri. Travelers

were also enticed by the figure of a stout man with a toothsome

smile, carrying a chicken on a platter.

* * * * * James William Chaney was born in Hickman County, Kentucky on January 23, 1881. He was married in 1902 to Miss Sue Ingram, and to this union two sons were born, Emory and Ray. The Chaneys left Hickman County in 1918 and moved to Arkansas. On June 7, 1924, the Chaneys were on their way back from a trip to Colorado. They arrived in Wright City at breakfast time and stopped for ham and eggs at Bill Fricke’s restaurant, the Silver Moon. At that

moment, Chaney was a bit unsettled. He had sold his stock farm in

Arkansas and taken his family to Colorado with the idea of

relocating there. But he changed his mind and they were on their way back to Arkansas when they stopped

at Wright City.

J. W. Chaney, called "Big Boy" because he had

been the biggest member of his family, wanted to give his customers the kind of

food he liked, and give them all they could

eat. One of the things he liked was fried chicken. So he offered

fried chicken, cooked the way he liked it, and served family style,

with plenty on the platter and plenty more where that came from. Coincidentally, on the day J. W. Chaney bought Bill Fricke’s Silver Moon restaurant, the contract was signed for the construction of Route 40 through the Wright City area. The highway engineers routed the road a block away from Big Boy's Restaurant, but that was alright with Chaney. The space, with its seating capacity of 14, four at the counter and 10 at the tables, was getting too small. If the highway wouldn’t come to him, Chaney would go to the highway.

Chaney bought a

building owned by the Masonic Lodge and remodeled it, with the

restaurant downstairs and a hall for the Masons upstairs. The new

restaurant opened on July 4, 1925. Signs went up on the highway with

the figure of a stout man with a toothsome smile, carrying a chicken

on a platter. Travelers followed the signs to Big Boy’s, where everything was served

family style. "Satisfy the Hungry

Customer" was Chaney's motto, and the

hungrier they were the better. It was easy to remember "Big Boy" Chaney. Not altogether because of his size, for he carried his 275 pounds lightly. Mostly it was because he was a friendly man who welcomed wayfarers heartily and, having fed them, sent them happily on their way.

It was the usual thing for customers to drive

the 50 miles from St. Louis for a meal at Big Boy’s Restaurant, and

not unusual for Kansas City people to make Wright City the objective

of a day’s driving, turning back after filling up on fried chicken.

Frequently, there were guests from greater distances. Chicken

dinners were featured at $1, with all the chicken you wanted to eat.

Drinks weren't an incentive; Big Boy didn’t believe in that. He

didn’t serve them and he didn’t permit alcohol to be brought in.

After a while, Big Boy's needed more room. The Masons moved out and Chaney remodeled the building again, adding additional dining space. Eventually, the dining rooms accommodated 100 customers. In 1940, J. W. Chaney, the big man with the big heart, died of a heart attack at the age of 59. But from the beginning, Big Boy's Restaurant had been a family affair, and it continued on that way. Chaney's sons, Emory and Ray, divided the management of the restaurant and their mother supervised the cooking. When a stranger came in and asked for "Big Boy," Emory would step forward and say he was one of them. It took a lot of chickens to feed Big Boy's hungry customers family style – 40,000 a year in normal times. On summertime Sundays, it was not unusual for 600 to be served. At rush times, the cooking was constant and the serving without delay. At other times, meals were served within 15 minutes. In 1945, the business had expanded to the point where the Chaneys decided to raise their own chickens in order to have an ample supply at all times. In October of 1948, a new section of Highway 40 was opened which moved the highway a block north of Big Boy's. But Big Boy's had already decided to move with the road and had erected a modern new building adjacent to the highway, which opened for business on November 13, 1948.

The new building was all on one floor and had a

greater seating capacity than the old one. It was 135 feet wide by

60 feet deep, and was surrounded by a parking lot that could

accommodate 200 cars.

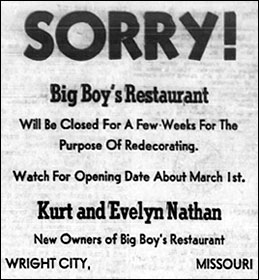

In 1962, after owning and managing Big Boy's for 38 years, the Chaneys sold their restaurant. While business was still booming, they were ready to retire. They continued to operate the restaurant until Christmas Eve, at which time the new owners took possession, and the business was closed for redecorating and remodeling.

* *

* * *

The restaurant was sold to Kurt Nathan. Nathan, an interior decorator in St. Louis, had bought 102 acres of land in Wright City in 1952 and got to know Emory Chaney. When he learned that Big Boy’s was available, he asked his daughter and her husband, Lola and Ed Baseel, to leave St. Louis and go into the restaurant business with him. The Baseels didn’t seem like the ideal couple with whom to entrust the legend of Big Boy’s. Ed was a plumber in South St. Louis; Lola was a housewife raising two young daughters. Aside from having no restaurant experience, they weren’t exactly typical Wright City society, not the kind of people you’d expect to be running a country restaurant in a rural community of 943 souls.

"The idea was a little frightening," Lola said,

"and it wasn’t made overnight. We discussed it for three or four

months and decided the country would be a good place to bring up the

kids." Although Kurt Nathan said he’d stay around for three or four years to help the Baseels break into the business, he got his fill after six months, said "It’s all yours!" and went to Florida. So the Baseels were on their own. They put themselves through a crash course in "How To Run Your Own Restaurant" and somehow it all came together and worked. What helped the Baseels the most was the "farm system" the Chaneys had developed over the years. The Chaneys had groomed three generations of employees to work in the kitchen or wait on tables. When the Baseels took over, they merely had to tap the resources that were already there. One of the keys to Big Boy’s success was the cooks who created the dishes from scratch with the same careful attention they put into a family meal at home. Stooping over stainless steel counters in the kitchen, white-haired women cut up chickens with large scissors and made soup and marinated cole slaw. Elda Witthaus had been with Big Boy’s for 24 years; Mary Lee Bishop, a small, shy woman with 15 kids, had put in 50 years of service.

Under the Baseel’s direction, Big Boy’s

continued to flourish. Although they had redecorated the dining

room, remodeled the kitchen, covered a rear wall with a 25-foot oil

painting of the old Chaney farm, put in a bar and added steak and

fish to the menu, the restaurant hadn’t changed much from the days

when Big Boy himself was frying up chicken in the kitchen.

On a typical Sunday, the restaurant would feed about 1,000 customers, most of them people who had made Sunday dinners at Big Boy’s a family tradition. When the 180 seats in the large, rectangular dining room were filled for a solid nine hours on Sundays and during the post-game hours on football Saturdays, the restaurant hummed and buzzed with diners gleefully clutching at large platters and bowls of food that were continually being brought to their tables by a crew of 25 waitresses. The Baseels were warm, friendly hardworking people who were highly visible in the dining room. There had been times when Ed had loaned his Cadillac to strangers whose own car had broken down on the highway. There were times when the Baseels have picked up the check for locals who had been down in their luck. They were trusting and gracious. Big Boy's Restaurant was known throughout the nation. Craig Claiborne, the noted gourmet of The New York Times, lauded Big Boy’s after a trip to the hinterlands to discover "decent dining places outside the metropolitan areas."

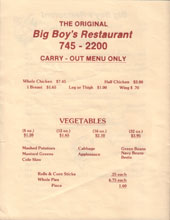

* * * * * In 1985, Big Boy's changed hands again. After Ed Baseel suffered a heart attack, the Baseels decided they could no longer run the restaurant. After 23 years as owners, they sold Big Boy's to Scott and Sally King, and their son Kevin. "Even though I just took over this place in 1985, I know there’s a lot of tradition surrounding it, and I’m trying to keep up that tradition," said Kevin King in a 1989 interview. "For instance, we still do the family style chicken and eight vegetables that they’ve always done. And we’ve added a few meats for those who don’t like chicken." Family-style meals were offered each evening and for lunch on Sunday. "You can choose either fried chicken, fried cod or ham," said King. “Or you can have a 12-ounce strip sirloin. But you don’t get 'all-you-can-eat' of the steak. We couldn’t afford to do that."

"We’ve found that a lot of people just come for

all the vegetables," King said. "But they also like the chicken. In

fact, 90 percent of our customers order the fried chicken, and the

majority get the white meat."

* * * * * State investigators walked into Big Boy's after the busy lunchtime period on April 20, 2005, flashed their badges and asked to speak to the restaurant's operator, Kevin King. After talking with the investigators, King told employees that the restaurant was closed. The investigators stayed long enough to let the customers already there finish their meals. "We are closed temporarily," said a paper sign taped on the restaurant’s front door. "Please accept our apology for any inconvenience."

The state said the restaurant owed more than

$30,000 in sales tax. Longtime workers at the restaurant said they

doubted the interstate landmark would open again. They were correct.

Two unsuccessful attempts were made to get the restaurant on the

National Register of Historic Places.

In January of 2011, Wright City purchased the 2.5 acre site for $170,000 and started moving toward demolition. The mayor said the city was considering using the property for a new city hall and police department. In June of 2011, the city opened the restaurant to sell the contents, including the long wooden tables and chairs.

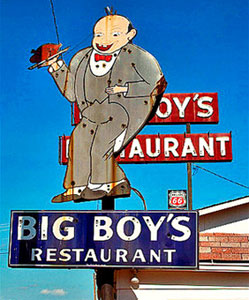

But the iconic outdoor sign depicting a smiling

buck-toothed man, wearing a gray tuxedo and holding a platter of

chicken was not among the memorabilia. Officials said it had been

gone for several years, and they weren't sure what happened to it.

Copyright © 2017 LostTables.com |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||