|

Golden Fried Chicken Loaf Mina Frieda Wolf was born in Baden, Germany in 1902, the daughter of Theodore and Mina Katharina Wolf. She immigrated to the United States in 1903, and by 1910 was living with her parents in St. Louis. At the age of 19, she married Virgil Bratton, who was working as a tailor. Mina Bratton was the subject of a feature article in the Sunday, April 12, 1936 St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

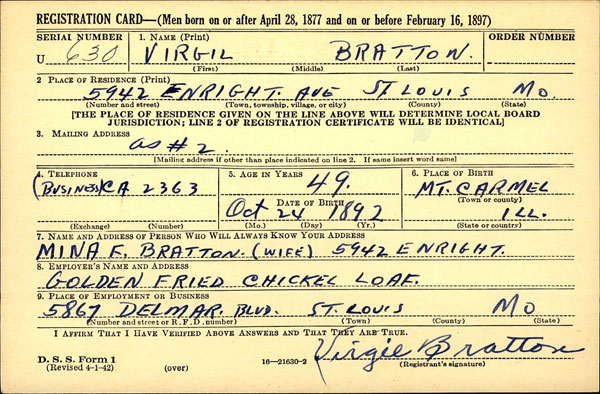

While the 1936 article refers to its

protagonist as "Miss Bratton" throughout, Virgil Bratton was still

her husband in April of 1942, the two living together at 5942

Enright. Virgil Bratton would die of pneumonia in September of 1943.

The Globe-Democrat article describes Bratton's transformation from stenographer to restaurateur.

The article goes on to recount the opening of Bratton's initial fried chicken restaurant.

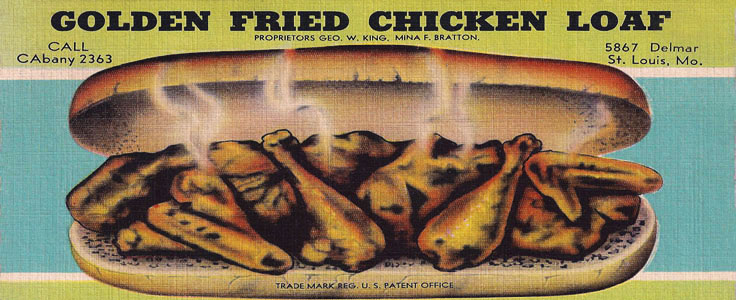

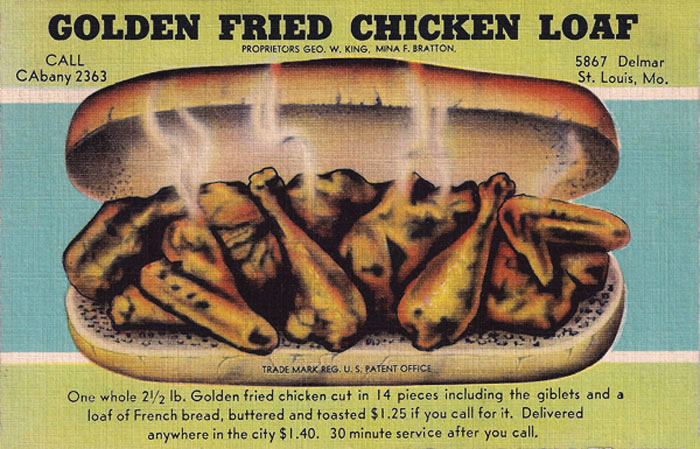

Bratton's "fried chicken loaf establishment" – Golden Fried Chicken Loaf – opened at 748 Hamilton Avenue (not DeBaliviere) in June of 1933. But it wasn't a "one-woman enterprise."

Golden Fried Chicken Loaf quickly outgrew its

Hamilton location. On August 25, 1933, the St. Louis Star and

Times reported a storeroom at 5631 Delmar had been leased "to

the Golden Fried Chicken Loaf Co. of which E. R. Pratte is

principle."

Elmer R. "Al" Pratte was indeed Bratton's partner in the nascent fried chicken business, and on January 25, 1934, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that Bratton had sued him for greater management participation.

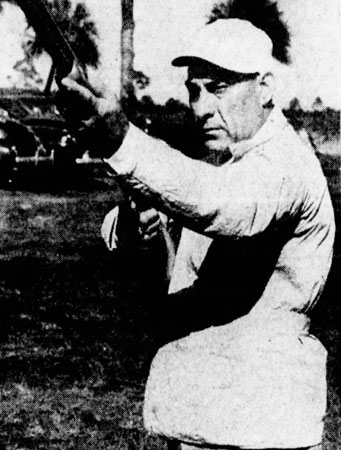

Pratte was a sportsman and would become a nationally-known trapshooter. While Bratton claimed she had heard about the fried chicken loaf from a "friend returning from Chicago," it's possible Pratte brought the idea to St. Louis from Tampa.

In 1932, Tampa's Red Mill restaurant advertised

a "large disjointed chicken, dipped into a creamy batter and fried

to a delicious brown, then inserted into a toasted loaf," calling it

a "Fried Chicken Loaf." The restaurant featured home delivery, as

did Bratton's.

Whether it was Bratton or Pratte who brought the fried chicken loaf to St. Louis, the concept was a success. After moving to 5631 Delmar on September 2, 1933, Bratton moved her restaurant to a still larger space at 5867 Delmar in early 1935.

Meanwhile, Pratte relocated to Florida and

registered "Golden Fried Chicken, Inc." in June of 1934. His Miami

restaurant successfully served "fried chicken between a whole loaf

of toasted bread" until he died in 1953.

By 1936, Bratton's fried chicken business was running 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, and employed an average of 13 people and seven delivery boys. But Bratton learned that frying and selling chickens was only one phase of her business.

Bratton opened her own chicken raising facility at 3512 Brown

Road in St. Louis County. It was a long, two story barn-like

structure erected in the rear of her home. It had a capacity of

15,000 chickens and it was kept running night and day to keep her

frying pans full at the Delmar address.

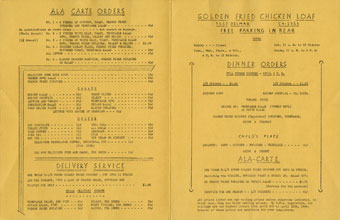

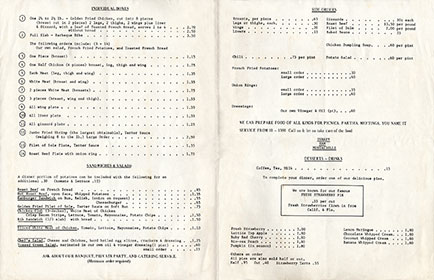

Bratton's "fried chicken loaf" was a chicken weighing exactly two pounds, cut in exactly 14 pieces, fried exactly seven minutes in deep vegetable oil at exactly 375 degrees and then packed between the halves of a special French loaf of bread, toasted exactly so many minutes. Wrapped and boxed, it was rushed to the customer piping hot.

In the beginning, Bratton offered only delivery

service. In 10 minutes flat, after an order was received by phone,

freshly fried chicken was on its way to the customer. From one to

half a dozen chickens made up the usual order, although once Bratton

fried 2000 chickens for a school picnic. Eventually, Golden Fried

Chicken Loaf added sit-down restaurant and carry-out service – and

did away with deliveries.

After her first husband died, Mina Bratton

married Omar Gerald Evans. The couple had two children, Omar Gerald

Jr. and Mina Annabelle, who worked at the restaurant on weekends

when they were older and in the summer when they were home from

college.

In 1947, Mina Evans remodeled her restaurant, expanding into the adjacent property at 5865 Delmar. Seating capacity increased to 165 diners, with a large private dining room for meetings and parties. The fried chicken served at Golden Fried Chicken Loaf was something special. Charles Dohogne worked there in the early 1950s, while in high school.

Golden Fried Chicken Loaf was also famous for

its chicken dumpling soup. German-style spaetzle noodles were

pressed through a colander into a hot chicken broth. Pieces of the

free-form dumplings would flake off, thickening the deep-yellow

broth. The spicy soup, which often traveled home in one-gallon glass

jars, was addicting.

Charles Dohogne worked 12 hour days on weekends and long nights after school. He was the dish washer/potato peeler/slaw maker.

On Sundays, streams of customers would enter the restaurant through the back door and line up in a crowded hallway to pick up their carry-out orders. They'd inch up to a low counter, underneath which were shelves filled with Golden Fried Chicken Loaf's famous pies. Charles Dohogne remembered the woman who made those pies – lattice topped apple, deep red cherry, hothouse rhubarb, coconut whipped cream, chocolate whipped cream, lemon meringue and more.

Mina Evans' Golden Fried Chicken Loaf thrived throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Charles Dohogne had vivid memories of his boss.

In 1969, an investment group headed by Ben Fixman and Albert Goldstein formed Country Foods, Inc. and purchased Golden Fried Chicken Loaf from Mina Evans. The group planned to build a second restaurant in St. Louis County to serve as a pilot for a chain of franchised fried chicken restaurants. The franchise would include full-service restaurants and smaller fast-food carry-out units. Mina Evans had a five percent stake in the company.

By April of 1972, a second Golden Fried Chicken

Loaf restaurant had opened at 12953 Olive, in the Olive Arcade Plaza

at Fee Fee. Early in 1973, Mina Evans' longtime Delmar restaurant

was shuttered and replaced with a second new location at 9773 Olive,

at Warson. Three more restaurants were in the planning stage. But the new endeavor was destined to fail. While the franchised restaurants sold Mina Evans' fried chicken and pies, she was no longer the driving force behind the business. The Golden Fried Chicken Loaf at Olive and Warson closed in 1981. That same year, Omar G. Evans, Jr. tried unsuccessfully to resurrect the restaurant at Olive and Fee Fee. It closed by early 1985. Mina Evans died in 1991.

You can hear more about Mina Evans and Golden Fried Chicken Loaf in the Lost Tables Podcast Series.

Copyright © 2024

LostTables.com |

a