|

Queeny Tower

Barnes Hospital opened on December 7, 1914.

"Located on Kingshighway at Euclid avenue, near where Kingshighway

turns west at Forest Park," the hospital building was four stories

in height, with four wings projecting toward the south. On the west

was the private room pavilion, offering suites

with baths for more affluent patients.

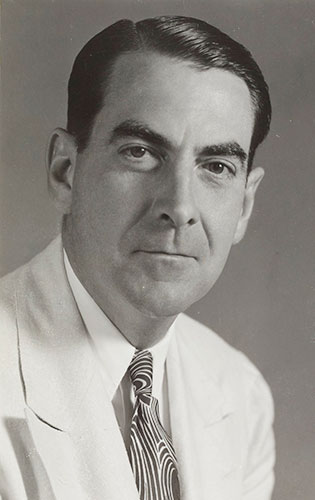

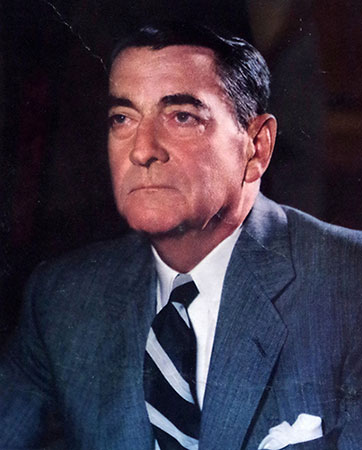

Barnes Hospital thrived and, partnering with the Washington University Medical School, developed a national reputation. But by 1960, the hospital was operating at a deficit and its infrastructure was aging. The hospital's mission to care for indigent patients was at odds with the rapid rise of private health insurance. And while the School of Medicine had constructed multiple new buildings in the complex for its clinical operations, Barnes had not made a major addition since 1931. * * * * * In 1960, Edgar Monsanto Queeny retired as the chairman of Monsanto, the company his father had founded. In 1961 he became chairman of the board of trustees of Barnes Hospital. A shrewd businessman, Queeny was troubled by the operating deficit at Barnes and the state of its facilities.

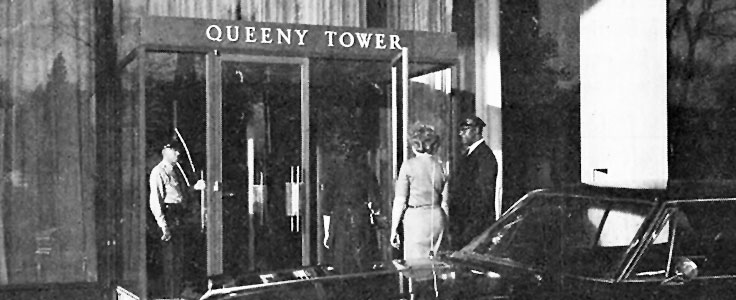

Queeny announced an extensive expansion and modernization project, which included an 18-story tower to replace the 3-story private pavilion on Kingshighway. The new building's upper floors would provide upscale "hotel rooms" for self-care patients, as well as for the family of patients from out of town.

Queeny put $4,500,000 of his own money into the

$9,000,000 tower and steered it into realization. And when the new

building was completed in 1965, it was aptly named Queeny Tower.

Many saw Queeny Tower as a symbol of a new approach in health care – treating the patient as a whole person, not merely a bundle of medical needs. Others simply saw it as a way for sick rich people to avoid sick poor people. Either way, with its original artwork, wood paneling and plush carpeting, Queeny Tower was as swanky as a hospital could get, offering its affluent patients services such as manicures and pedicures, hair styling and room service. There was a swimming pool on the 18th floor, nestled under a bronze-and-glass solarium roof. One floor below was the tower’s full-service restaurant. In a March 15, 1966 article, St. Louis Post-Dispatch columnist Jack Rice provided a colorful description of the upscale Queeny Tower, including its 17th floor lounge.

The restaurant housed on the 17th floor of the tower was modeled after a Swiss chalet, complete with multicolored wood and a roughhewn look. In addition to the lounge, there was a main dining room, a coffee shop and a private dining area. German-inspired cuisine was featured on the menu.

The cheerful Bavarian themed coffee shop looked

east over the rooftops of the city. In 1973 a breakfast egg cost a

dollar and coffee forty cents.

The main dining room was on the west side of

the building. Its floor-to-ceiling windows offered stunning views

across Kingshighway into Forest Park and down on Steinberg Rink. In

the winter months, especially when forecasts called for snow or icy

roads, people would come up and have dinner and a drink, and keep

their eye on the highway traffic below.

Starting in 1980, the Queeny Tower dining space was renovated and modernized, with a more contemporary decor. A second entrance was added from the newly constructed West Pavilion, via a skywalk. On a typical Sunday morning, classical music playing and the smell of bacon frying filled the crowded dining room, as a long line of people waited to be seated. In the evening, the dimly lit dining room attracted large crowds of patients, employees and guests. With hardwood floors, white tablecloths, music playing in the background and candlelit chandeliers, the restaurant was a popular dining choice. The dinner menu included steaks, a shrimp platter and a chef salad with Mayfair dressing. The carrot cake was legendary. But Queeny Tower’s signature dish was served at lunch.

The Prosperity, which was brought over from the Mayfair

Hotel where it was originated, was an open-faced sandwich made with white bread, turkey

breast, honey ham and bits of crispy bacon, covered with a special

cheese sauce and topped with crumbled parmesan cheese. It was

broiled and served on a steaming not plate. It stayed on the menu

until the chef who made the cheese sauce left, and the sandwich left

with him.

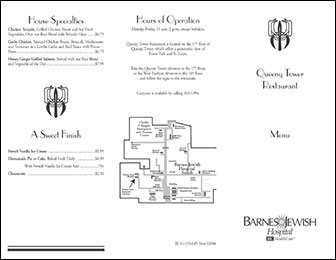

In 1984, the Tower menus were "revised after extensive marketing research to better meet the needs of Barnes patients, visitors and medical and professional staff." The new dinner menu included filet mignon, lobster, shrimp tempura, baked fillet of sole, seafood fettuccine, fettuccine alfredo and breast of chicken. It also included "light" meals such as eggs benedict, a croissant sandwich platter and a chef salad. The revised lunch menu included old favorites like the Prosperity and new items such as croissant sandwich platters, quiche Lorraine and a bacon cheeseburger. Light entrees such as eggs benedict or spinach salad were also available during lunch. A new breakfast menu specialized in eggs benedict and fresh omelets, and offered such standard fare as fruit or plain pancakes, French toast and side orders of any style egg, hash brown potatoes, bacon, ham or sausage, plus hot and cold cereals and a variety of fruit juices.

In 1997, the Queeny Tower

"hotel" closed and

business in the restaurant began to decline, until eventually only

lunch was served.

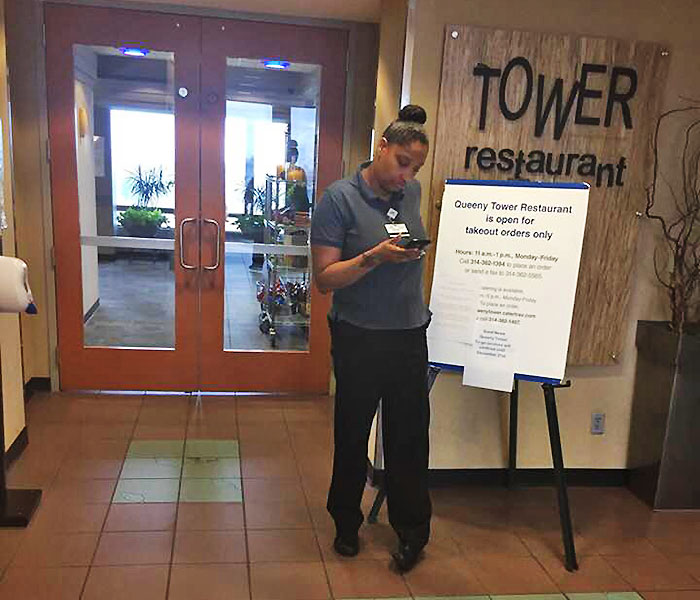

The Queen Tower restaurant closed its dining room

doors on November 14, 2016. The restaurant remained open at lunch

for carry-out orders for employees and also

for catered events. But the days of walking in, sitting down,

filling up and taking in the scenery were gone.

Edgar Queeny died in 1968. His tower survived until 2020, at which time it was slated for demolition. Officials explained that Queeny Tower was "unable to be retrofitted for modern technology and didn’t meet seismic standards required." They said a planned new tower would "enable the expansion of the heart and vascular; neurology and neurosurgery; transplant; trauma and critical care; and general medicine programs" of the hospital.

There was no mention of hotel rooms or a

restaurant.

Copyright © 2020 LostTables.com |