|

Garavelli Joseph Garavelli was born Guiseppi Garavelli on August 28, 1884 in the northern Italian municipality of Bassignana. In 1901, at the age of 17, Garavelli's father paid his way across the Atlantic. Garavelli's two older brothers, Ben and Charlie, had been in the United States for 10 years. They had a bar and restaurant at 49 Bleecker Street in New York City, and Joe Garavelli went to work for them as a bus boy. "But I got homesick," he confessed years later. "I got so homesick I couldn’t stand it, so I told my brothers they had better send me back home. They did." Before Garavelli boarded the ship in New York, he stopped in Macy’s and bought a new hat, a handsome felt of dark blue. "When I got back to Italy my friends all laughed at me," he recalled. "They wanted to know why had I come back? I told them I had just gone to American to buy myself a new hat." In 1903, Joe Garavelli returned to the United States. His brothers had moved to St. Louis, and he joined them there. They owned a saloon at the northeast corner of Garrison and Washington. "I worked as a bus boy, scrubbed floors, did everything there was to do, and I was a lonesome kid." Garavelli could speak no English. His brothers spoke Italian, and most of their customers spoke Italian. Garavelli figured that if he ever hoped to get ahead he had to learn the language, so he got a job as bus boy at Tony Faust’s restaurant. In 1909, while working at Cafferata’s Cafe on Delmar, he became a citizen. By the end of 1912, Ben and Charlie Garavelli had opened a cafe at Grand and Olive; their "Garavelli's" would remain in business until 1979. Joe Garavelli again joined his brothers, working as a bartender. But he was destined to have a place of his own.

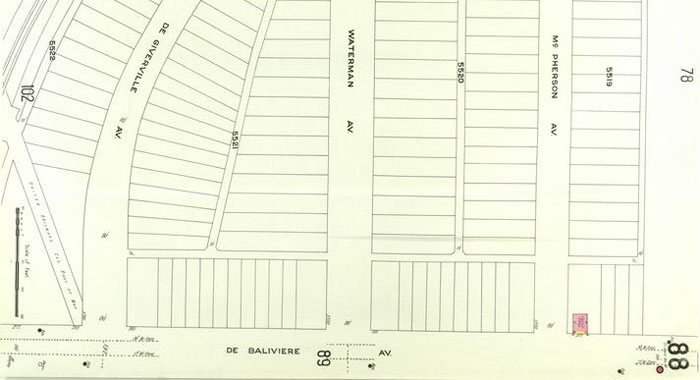

Garavelli knew of a vacant lot at the northwest

corner of DeBaliviere and DeGiverville that was owned by the estate

of Eberhard Anheuser, the father-in-law of Adolphus Busch. He

decided it would be a good place to open a saloon.

Garavelli thought otherwise. He figured the

population would keep moving west. His saloon would be two blocks

north of the entrance to Jefferson Memorial. It would be the "first

chance" for those leaving the golf links, tennis and baseball

grounds in Forest Park.

Garavelli went to Adolphus Busch with his idea. In those days a brewery would set a man up in business if it thought he had the qualities of a good saloonkeeper. Garavelli had become well known and well liked at Cafferata’s, and the brewery decided to go along with him. In 1913, the brewery put up the corner tavern, furnishing it with a splendid old fashioned bar and mahogany paneled walls. Garavelli was all set to go, only to discover that he couldn’t get a license. The few people living in the neighborhood objected to a tavern. Garavelli eventually obtained a license the following year, and opened at 5701 DeGiverville in the summer of 1914. As a concession to the opposing residents, he put no sign in front of his bar and no bottles or paraphernalia in the window that would assist passersby in identifying the place as a saloon. He also agreed that no women would be served.

After he opened for business, Garavelli began

to think he should have waited a while longer. About the only

company he saw was the motorman on the streetcar which looped at DeBaliviere and went back to town.

But when the neighborhood began building up, business picked up. The carpenters and bricklayers building houses in the area beat a path to his door with their beer buckets. Garavelli put a tent behind the tavern where the workmen could sit in the shade, eat their lunch and drink beer. When the workmen finished building and left, "the city crowd" discovered the tavern. Garavelli became THE place to go. Garavelli was beginning to enjoy steady prosperity when Prohibition came along. While some of his fellow Italians turned to bootlegging, he forgot about his bar and turned attention to his kitchen. When Garavelli was still working for his brothers, one of the things he learned was to make a good combination ham and cheese on rye. The casual observer might have thought one ham and cheese sandwich on rye was much like any other, but Garavelli would have told them otherwise. His customers agreed.

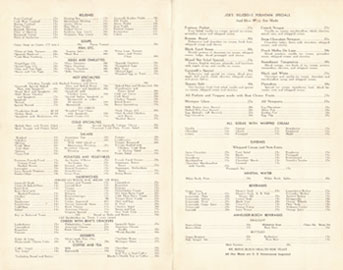

His business was built on one

ham, one hunk of cheese and one loaf of bread. One of Garavelli's

sandwiches provided a square meal for the average man, and it cost

15 cents. He added hot roast beef to the menu,

then various other dishes, including spaghetti and mostaccioli. On Fridays,

he served his famous filet of sole. Garavelli was the first to offer drive-in service in St. Louis, with seven waiters in white jackets taking care of the automobile trade at the curb. He also claimed to be the first to institute take-out service, which proved very popular. One could always rush over to Garavelli for ham and cheese and spaghetti when last minute guests dropped in. In 1925, Garavelli expanded his restaurant, erecting a new structure adjacent and to the north of his existing building.

The Italian Garden,

a large dining room with marble walls, a

crystal chandelier and a marble fountain, was added to Garavelli's saloon, and his restaurant became an institution. A tall and heavy-set man, Garavelli was always in his restaurant – that is, in the paneled room on the corner with the bar, where the ham and the roast beef were carved before his customer’s eyes. Garavelli appeared only infrequently in the large and more ornate adjoining dining salon. In the dining room one could get a full-course dinner, but Garavelli regulars also preferred the old bar with its buffet. It had reached the point where each day there were 15 carvers serving up to 75 baked hams, as many as 50 big, rare and juicy roasts of beef, and nobody knew how much spaghetti with meat sauce. It was one of the memorable pleasures of life to step up to the buffet, watch the white-coated carvers with long, razor-edged knives cut away thick and juicy slabs of baked ham with masterly precision, dip big slices of rye bread into hot, red-eye gravy and put the sandwich together with the delicate care of men who loved their work. Then one proceeded to a little counter at back where Garavelli himself, wearing a white jacket, stood behind a counter loaded with deviled crabs, kosher pickles, potato salad and coleslaw. Behind him was the icebox filled with cheeses and sausages; at his right and left were piles of French and Italian bread.

He greeted everyone with,

"Hello, my friend," or in the case of a younger customer, "Hello, my

boy." And for the youngsters, there was always a breadstick to

munch on.

That was one face of Joe Garavelli, the face seen by customers who came in the front door. There was another face seen by those who came to the back door. It was the face of compassion. Garavelli used to say, "Anyone can eat who has money." But during the depression there were many who did not. Garavelli never turned down a man because he was broke. When the depression was at its worst, Garavelli handed out as many as 150 box lunches a day at his back door. Four times a year, Garavelli treated the children at Shriner's Hospital to ice cream and cake, and every summer he would go to Boy Scout camp and cook a feast of baked ham, chicken and spaghetti for the boys. Garavelli learned that a collection of rare books assembled by David Bryce, a Scottish architect, was being offered for sale. His restaurant had become a popular hangout for students from Washington University. When he learned how much these books would mean to the university as a reference library, he donated $10,000 to buy the collection, with the understanding that his name should not be revealed.

In 1930, Garavelli was decorated by King Victor Emanuel as a Knight of the

Crown of Italy in recognition of his charitable work. For the next 10 years, Garavelli continued to preside between the herring and the coleslaw, surrounded by signs he liked to put around the place. They all started with "Joe says" and conveyed such messages as "DON'T ASK FOR CREDIT" and "NO CHECKS CASHED," neither of which meant anything as Garavelli would cash a check for or give credit to anyone.

One of his signs read "DON'T

TALK TO

THE MOTORMAN."

He put it up because one day, while he was slicing meat and engaged

in conversation with a customer, he almost sliced of a thumb. In 1941, at the age of 57, Joe Garavelli retired from the restaurant business. Even though in good health, he decided it was time to "take things easy."

Garavelli

tried to sell his restaurant to his employees, but ended up selling

the business to August Sabadell, the catering manager of the Chase

Hotel. Sabadell took a 15-year lease on the property, which was

still owned by Anheuser-Busch. In 1952, Stan Musial and Julius (Biggie) Garagnani purchased the Garavelli property from Anheuser-Busch, including the lot and two-story building. August Sabadell continued to operate the restaurant, his lease not expiring until 1956. The business changed hands multiple times after that, going downhill as customers moved westward and the neighborhood deteriorated. The restaurant was auctioned off piece by piece in 1974. The 84-foot bar was sold for $70, a steam table that cost $12,000 to install brought only $275, bar stools went for $3, water glasses 5 cents apiece, and salt & pepper shakers 16 cents. The chandelier of hand cut prisms that once gleamed in the dining room brought $5,250.

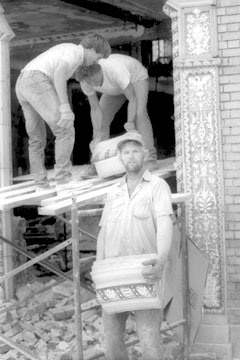

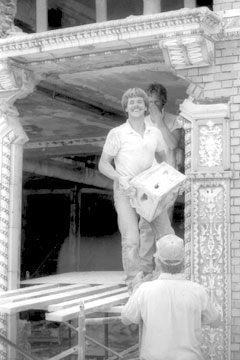

The building itself was demolished in 1987. All

of the buildings on the block were razed – the so-called "DeBaliviere

Strip," which included Garavelli, the Stardust Lounge, the Apollo

Art Theater and Sorrento's. Preservationists worked to save 28,000

pounds of multicolored terra cotta that adorned the top of the

building and its front windows.

Over the years, multiple Garavelli's

restaurants opened (and closed) throughout the area, including

at Westport Plaza, on Manchester in Maplewood, on Manchester in Rock

Hill and on Chippewa. The Rock Hill and Chippewa locations were

institutions in their own right.

Joe Garavelli died on October 1, 1968 at the age of 84. While he had no official connection to the business after he sold it in 1941, he spent much of his retirement at the restaurant. Most any day, between late morning and early afternoon, he could be found there drinking coffee, talking to old friends and greeting customers with his customary, "Hello, my friend." His establishment on the corner of DeBaliviere and DeGiverville was a friendly place. Hundreds of St. Louisans hoped for years that he would take charge again. But the man whose ham and cheese on rye had the world beating a path to his door never did.

Copyright © 2022 LostTables.com |

||||||||||||||||||||